OK, I need your help. I have been playing around with this idea of triangulation (possibly not the right term) for a couple of months. Lilia has written about it to help me, but now I need my network to help me sharpen my thinking. Can you please read this and give me your feedback? THANKS

Triangulating for Success:

a practitioner’s experience using external networks to leverage learning and outcomes within organizations and institutions

Introduction

Organizations and institutions are ostensibly places for learning and getting work done. But sometimes individuals are blocked from achieving those goals. Blockages come from unsupportive superiors, a risk-aversive culture stifling innovation, a need for taking of credit by management, a lack of diversity of opinion and thought amongst staff, and simply the inertia of large organizations. The structure of organizations is often to replicate what is, rather than evolve into what it might need to be next. This can block success. In the context of expanding learning opportunities, one option is to triangulate outside the organization to enable increased learning within.

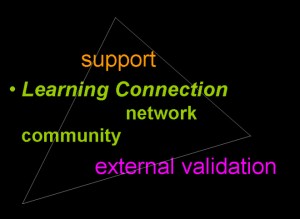

In an informal evaluation of successful collaboration, learning and teaming initiatives in a variety of contexts, the author and her collaborators have noted a pattern for supporting learning and getting work done: triangulating one’s work with external colleagues, communities and networks. This pattern has three phases: support and personal validation, connection to a community and/or network for practice and learning and finally, external validation. This paper examines each phase, reflects on how this external triangulation relates to some exemplar learning theories, and finally, offers some examples and suggests how designing this external triangulation into learning and work efforts can increase project success.

Blockages to Innovation and Learning

In working with knowledge sharing and learning initiatives within international non governmental organizations (NGOs), the author has observed a pattern where talented internal practitioners have struggled to spread innovations, engender learning required for successful work, and in general, been stopped from excelling.

The Three Phases

Phase 1: A mirror and a candle

Working in isolation and often without supportive management, practitioners feel alone. Isolation has been shown to be a factor in reducing a practitioner’s sense of professionalism and agency.1 Ideas and learnings, initially thought to be generative, start to be doubted by the practitioner. Often there is a diminished sense of worth, and an under-recognition of their own assets.

When an external practitioner connects with the internal practitioner, there is a chance to “hold a mirror” up so the internal practitioner can see the value of their work and their own professional skills. This process of validation can provide a great deal of self confidence and energy in what might otherwise be an unsupportive, or minimally supportive environment. It is like an infusion of courage and confidence.

The connection with an external practitioner then allows a sharing of ideas, and the beginning of a peer coaching or support relationship. This is the candle that lights the way to “next steps.”

In a large international NGO, a practitioner has developed an innovative new way to share learnings within and without the organization using new social media tools and collaborative practices. She feels her idea will accellerate knowledge sharing, increase learning and reduce duplication. However, she is blocked from implementing her ideas because her management has insufficient experience with social media, a reluctance to take a risk on a new idea, and is not fully convinced that the knowledge sharing would protect his team’s “competitive advantage” of being a gate keeper for knowledge flows. While this concern is counter to the organization’s mission, it is consistent with the way “business is done” internally.

Feeling discouraged, but not ready to give up, the practitioner connects with an external practitioner who enthusiastically encourages her, helping her see the power of her own ideas and experience. Instead of thinking her ideas are bad, she realizes they are legitimate but that she needs more examples of success from other organizations and a validation of her technical approach.

In this first step, an isolated practitioner moves from potential, to action, tapping that potential through support and affirmation.

Phase 2: A community of practice, a network of learning

The second phase is the recognition that the practice lives not only in the experiences of the internal and external practitioner pair, but in larger community or network of practice. According to Wenger2, a community of practice is ”Communities of practice are groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly.” The importance in this context is that isolated practitioners, such as early e-learning innovators, need the diversity of experience of a wider group of people. Organizations often foster homogeneity which supports uniform execution of plans, but does little to support innovation. E-learning practices are still nascent and require the collaborative thought and practice laboratory with other practitioners. Innovators need access to ideas, real examples of practice, “critical friends” who can critique the ideas, support, coaching and “testing ground” for thinking out loud in a safe environment. They need time and space for reflection.

New web based technologies now provide visibility of and access to these networks of practice. From the “social networks” of Facebook and others, which appear to have no direct relevance to professional work, to specific professional networks, to loosely affilianted networks of bloggers, people can now find and connect to others. Even the social networks give exposure to professionals and participation in these networks should not be automatically discounted. However, it is important to know how to present one’s professional online identity and effectively use the networks.

The external practitioner then connects her to an online network of practitioners working in other related organizations. Through effective internet searches, activation of personal networks linked via online social networks, the two reach out to other practitioners who enthusiastically offer their experience, feedback and support.

Phase 3: External validation

The interaction with a community/network of practice leverages the learning of the individual practitioner, allowing them to build their skills, reflect on their practice and gain constructive feedback. However, this does not overcome the blockages preventing acceptance and spreading of new practices within the organization. They transform the individual, but not yet the organization. This is where the third aspect of external validation comes into play.

The familiar expression “you can’t be a prophet in your own land” reflects a common pattern of organizations not valuing innovation from within, instead relying on external “experts.” However, when internal work is validated externally, it is given more attention and credence. For example, consider the situation where an innovative staff member, frustrated with a lack of internal support, leaves an organization, becomes a consultant and is subsequently hired by their old organization as a valued consultant. They are paid more, given more respect, and most important, they are listened to.

While positive external “word of mouth” can give validation, internet based social media gives us a more visible medium to reflect on the work of the internal practitioner. This offers validation both publicly and validation available inside of/on behalf of their own organizations. External validation can affirm an innovation, or put subtle peer pressure on internal leaders to recognize the work/learning and respond to it (vs. block or ignore it.)

External validation can trigger management attention – even if this means management takes credit that actually belongs to their staff member(s). Once management recognizes the learning or innovation, there is a chance for it to take root and spread in the organization, triggering change that the one individual could not catalyze by themselves.

Finally, members of the network of practice begin to blog, write on their email list and web platform, about the work of the internal practitioner. This news filters back to the practitioner’s management, validating her ideas and giving them more reason and courage to support the new ideas and practices that they had previously resisted. She now has approval to begin a pilot project to test her ideas. Her management is further recognized for their innovation, giving everyone a tangible example that sharing knowledge and collaboratively working can provide benefit to everyone.

Strategies for Individuals and Organizations

By recognizing the power of external support from individuals, communities and networks, we can begin to design this triangulation into our work. This suggests some competencies and actions, as well as some pitfalls to avoid.

Competencies supporting triangulation

There are three important competencies: having one’s own online professional identity, scanning for related professional networks, and the willingness to “learn in public.”

Developing a public online identity as a professional is the first competency. “‘Digital Identity’ (DI) is a term to describe the persona an individual presents across all the digital communities in which he or she is represented5. (For more information about building an online digital identity, see “This is Me” for NGO Folks by the author. 6) Professionals need to establish their professional digital identity as a way for others to discern if they want to learn with each other.

One cannot tap into external support without knowledge of other practitioners and their networks. Scanning for professionally related communities and networks, engaging with them and reciprocating support to others are core competencies for triangulation. Being willing to ask for help, reflect on one’s own practice in view of others and accept constructive feedback are also important. In organizations where “being right” is more important than learning, this ability to learn “in public” with others may be difficult. But today, learning and innovation require us to become professional networked learners7. We simply cannot learn all there is to learn by ourselves – let alone filter and evaluate everything in the world. Digital tools create a flood of information. Only with our networks can we filter that flood. And only by willing to experiment and think outloud can we do this together online. Not everything can or will be done behind “closed doors” or “closed firewalls.” Ultimately, our reputations will not rely soley on what we accomplished, but also how we accomplished it and with whom.

Reciprocation of support and external validation of others is important for maintaining one’s reputation and identity in an external community or network of practitioners. While reciprocity in networks is rarely one to one, being known as someone who gives, not just takes, increases social capital and the availability of peer support. Robert Putnam described the value of this communally shared social capital as a cornerstone to society itself.8 One should never consider “one-way” triangulation. It is an ongoing interweaving of learning and support across the network.

Activities supporting triangulation

Triangulation can be designed both into projects and into personal practices. For example, during a learning project design, practitioners can include steps to identify external individuals, communities and networks that relate to the work and allocate time and other resources to tap into those networks. External actors can be included as part of project peer review and evaluation, creating natural linkages for support and validation. The inclusion of informal, ongoing publications sharing “work in progress” via blogs, micro-blogging or wikis can create additional windows for external triangulation.

Pitfalls to avoid

Triangulation is not without risks. There are two primary things to watch out for: transgressing organizational rules, norms and boundaries and the issue of who takes or gives credit to ideas and work.

Practitioners must not violate organizational rules about what can or cannot be shared outside of the organizational boundary. This may involve intellectual property, competition and other factors. These boundaries are often significant blockages themselves to innovation and learning, and organizations should be very careful about not overregulating. The value of openness often brings deeper and longer term rewards than a short term “holding tight” to ideas or a strong need to take credit for things.

Practitioners may also find that once their ideas are triangulated and validated externally, others in the network and even their own management may “take credit” for the ideas and work of the practitioner. While we hope that people aggressively work to recognize prior contributions, we know it does not always happen. The ideas in this very paper grew out of a myriad of uncountable and now untraceable ideas shared by colleagues and network acquaintances of the author. What of that attribution? It has flowed past, never to be recaptured. As a consequence, the credit may never fully land where it is deserved. This is a cost of working openly in and with the network.

Conclusion and Implications

Triangulating learning through external support from individuals, communities and networks can provide significant, low or no cost support to innovators and learners within institutions. This triangulation requires networking skills and a willingness to learn in public – even possibly loose part of all credit for one’s work. The rewards, however, are increased learning, practical experience and ultimately the ability to change not just one’s self, but one’s organization.

1 Barab, S., Kling, R., Gray, J., (2004) Designing for Virtual Communities in the Service of Learning, , Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

2 Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Leaning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

3 Engeström, Y. (1999a). Activity theory and individual and social transformation. In Y. Engeström, R. Miettinen, & R. L. Punamäki (Eds.) Perspectives on activity theory, (pp. 19–38). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

4 Efimova, L. 2009 Understanding Networked Professionals accessed November 29, 2009 at http://blog.mathemagenic.com/2009/11/09/understanding-networked-professionals/

5 This Is Me by OdinLab, University of Reading (Not quite sure how to reference y et) http://thisisme.reading.ac.uk/

6 White, N 2009. This Is Me for NGO Professionals, accessed November 29th, 2009 http://fullcirc.com/wp/2009/05/19/digital-identity-workbook-for-npongo-folks/

7 Efimova 2009 http://blog.mathemagenic.com/2009/11/09/understanding-networked-professionals/

Enter the Orton Family Foundation’s first Heart & Soul Photo Contest and help us and citizens of small cities and towns across the country celebrate, nurture and revive community

Enter the Orton Family Foundation’s first Heart & Soul Photo Contest and help us and citizens of small cities and towns across the country celebrate, nurture and revive community  Per many Twitter requests…. Happy Thanksgiving (US holiday, but spirit is universal).

Per many Twitter requests…. Happy Thanksgiving (US holiday, but spirit is universal).