A guest post by Philip Clark

(Nancy’s Note: Philip and I are members of this little community of practice focusing on the use of Liberating Structures in strategic planning and work. He has been generously taking the lead of crafting and building on these summaries of our learning sessions. THANKS, PHILIP!)

“Begin at the beginning,” the King said, very gravely,…”

Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

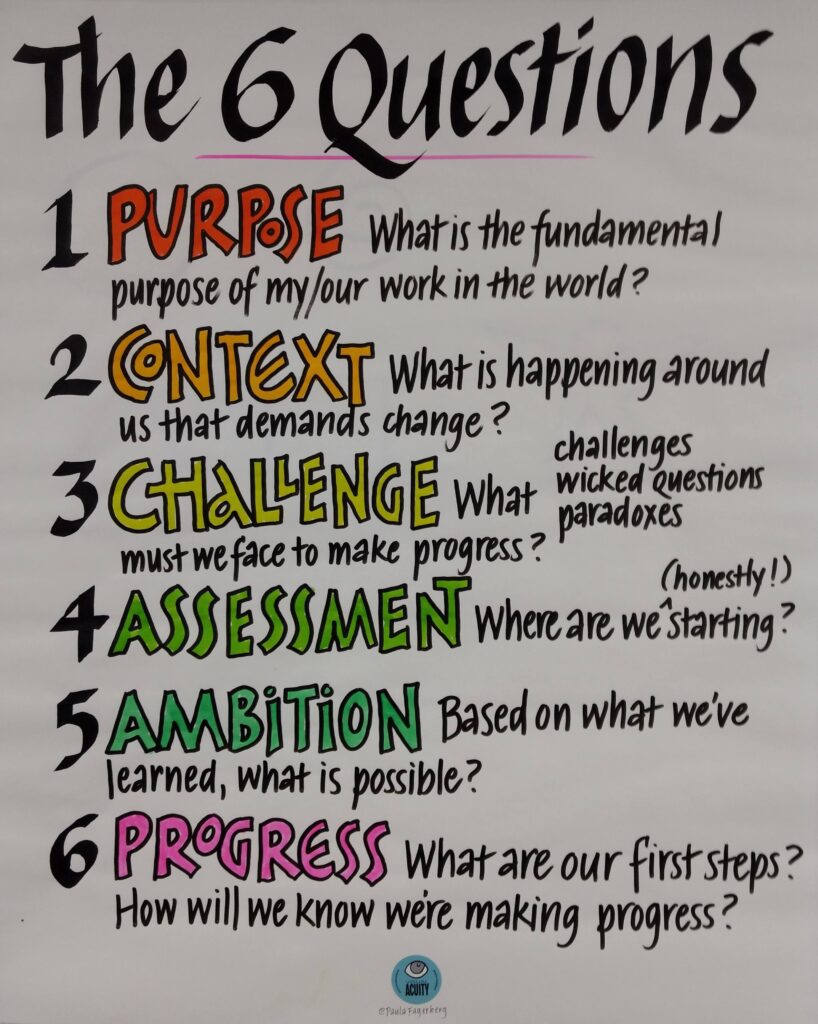

Within the larger Liberating Structures network there is a community of practice devoted to the development and understanding of Strategy Knotworking (SK), a set of six questions, often answered using various Liberating Structures (LS). SK lends itself to complex contexts and where there is a desire to engage everyone in planning.

This is the second installment (here is the first) of takeaways from the various conversations that we have been fortunate to have with seasoned practitioners on Strategic Knotworking (SK). Today, the celebrity is Fisher Qua.

Fisher started the session by recalling the beginnings of SK, reminding us that somehow Liberating Structures do not come out of hat or fully dressed like Athena from Jupiter’s head.

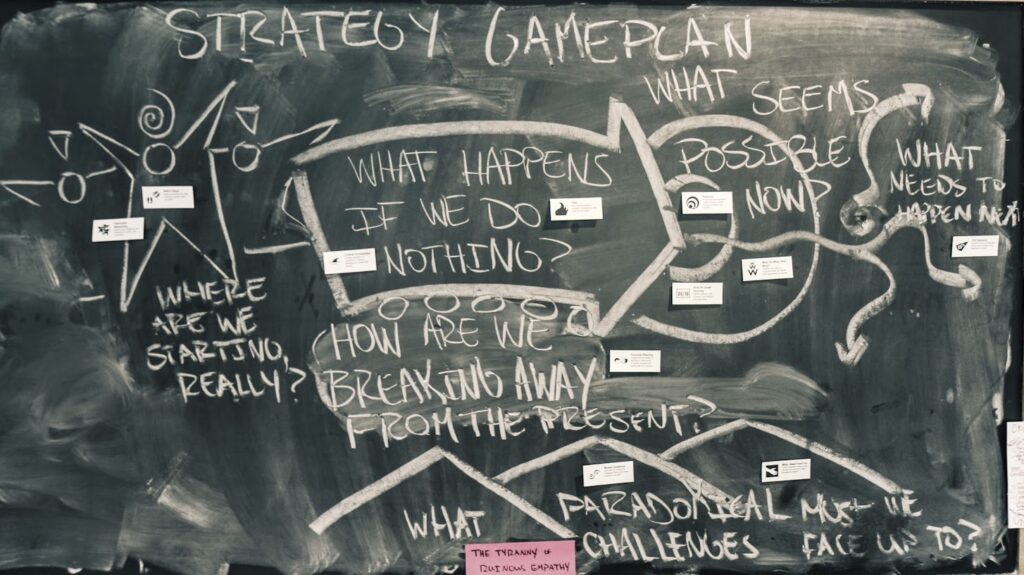

It started, he reminisced, with the incorporation of Core Prime questions as part of Celebrity Interview Riffs and Variation prompts options. Questions like : what is happening around us that demands creative adaptation? Given our purpose, what seems possible now? As for the first visual representation, it stemmed from the graphic gameplan of David Sibbet of the Grove and evolved into a mash-up of several approaches to strategy that Keith called Strategy Safari. (For the deeply process geeks, see here and here.)

Something changed for Nancy and others when she started looking at the process as a narrative weaving together the 6 questions to create a storyline that everybody could own and operate. Somewhere along the way, it got its name. Nancy wrote several blogs about it. Keith and Johannes wrote a long article, and then our community of practice got together.

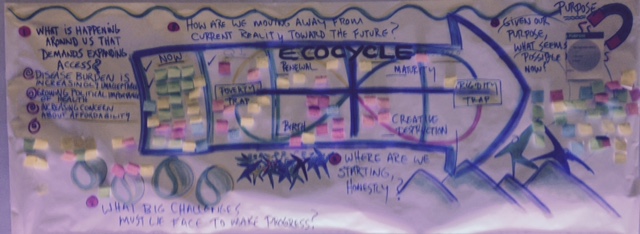

Nancy added the Ecocycle to the arrow which provided a structure to record things (questions, answers, observations, etc). At first, the idea was not to define a deliberate sequence but to use a bunch of LS to collect the responses so that people could see them.

Like most beginners I reckon, I first believed that SK was a somewhat linear process evolving from Purpose to Action and Evaluation in a series of well defined and logical steps. Listening to Fisher, Michelle, Lynda, and Barry (our other guest practitioners) I am amazed to see how malleable the structure is. The structure itself invites a large array of questions and prompts (see Michelle’s account), and can utilize many combinations and a variety of tools. It is malleable in how it can roll out over time, from 2-3 hours to days, either in a single session or spread over time. In the case discussed by Fisher (that of a business school) the process lasted 9 months with a medley of formats and both synchronous and asynchronous work.

Fisher’s story of a business school

The project explored all 6 questions and included quite a large design or core team (about 20 people) bringing together concerned stakeholders: undergraduate and graduate students, business school administrative staff, a couple local business owners, a couple of alumni, and associate, adjunct and full-time faculty fulfilling the need for requisite diversity and participation and, at the same time, embodying the first principle of LS “include and unleash everyone”.

The delivery was intricate.

The first part aimed at gathering people’s view on the various components of the SK process (Purpose, Context, etc) To do this, the Core team was invited to self-organize into pairs or trios and were tasked to interview at least 10 people in each of the areas of SK. For example, regarding purpose, they were asked to interview 10 people using 9-Whys. The same approach was applied for Context, Challenge, etc…

A half day online workshops were planned every two weeks to harvest and make sense of the material gathered during the week.

The second part of the project consisted of 2-day in-person sessions with rotating groups spending 3 hours at a time in structured interactions. For example, on day one, members of the business community and undergrad students came together and explored Context. In another session full-time and adjunct faculty had a chance to work on Purpose. There were other sessions where everybody came together simultaneously in the room and worked through Ecocycle. This took 2 x 3 hour half day sessions..

An interesting development happened around Purpose.

It was this writer’s bias that the purpose of an organization would be one and shared by all, but in the case of the business school different stakeholders had different purposes; for example between students and faculty, but also between faculty and the representatives of the business community. One can easily imagine a desire for employability versus an interest in academic inquiry leading to different purposes. At any rate, they ended up with multiple propositions which, after some consideration, were shown to express different positions at different scales within different contexts creating a sort of stepping stone towards Panarchy.

The same thing happened when Ecocycle was used to map the Baseline. The final result was four Ecocycles. One was Business School relationships, another Departments program, a third around different practices, a fourth related to curricular elements

Considerations

- SK can not only address the main elements of strategy (purpose, context, etc…), it can do it on several scales which, as far as I know, is uncommon and much-neglected in more traditional frameworks.

- Ecocycle can map different things such as activities, tasks, actions etc. It can be paired with Panarchy to look at the effect of scale on a given topic and look at progression/development over time, but it can also be used to zoom in on a single item within an specific Ecocycle if it appears too large or too obscure or too complex.

Execution is the Achilles heel

When the process ended at the business school, committees were created to carry on the actions identified in the sixth step of the SK process. But, as it were, things got “lost in translation” since nobody was willing to take operational responsibility. We had seen something similar in one of the cases that Michelle described, reminding one that if decision makers are often responsible for crafting strategy they are rarely involved or even interested in execution. This is all the more wicked that, at the outset of strategic work, the general expectation of teams and management often revolves around planning with little or no patience for introspection, connections, relations, or inquiry.

Given this state of affair Fisher muses about the possibility to add a macrostructure that would weave execution into SK. He calls it “Strategy Knotworking and Operational Knitting.” It consists of replicating the patterns used in the strategy design phase – core team, regular cadence of meetings, structured interactions – in the implementation phase. In his words, “to make sure there is an operational “function” with the organization that can pick-up knotworking where it leaves off.”

Practitioners like Lynda Frost use non LS strategy planning tool (in her case David La Piana’s Strategic Planning template) and a couple of follow-up meetings with the management team to ensure that actions are undertaken and monitored. And then, from a purely LS process, we have Henri’s meeting macrostructures. AsI would be very interested to learn about other ways to provide/integrate a scaffold regarding execution within or without the realm of LS.

Relational coordination

There is a sense among some practitioners that SK does not really make the grade as a strategic tool or process because it lacks mechanisms for implementation and allocation of resources. Said another way, SK may be good at strategy-thinking not at strategy-doing. But is this true?

It is indisputable that the tactical side of strategy is its ultimate validation. Without actions and measured outcomes, strategy remains a pie in the sky. But there is another side to strategy which Fisher calls relational coordination inspired by the Relational Coordination Research Collaborative at Brandeis University that few organizations pay real attention to and yet, as we shall see later, directly impacts performance.

In Fisher’s words relational coordination is “the practice of tuning into context, revisiting purpose in a way that multiple people are invited to respond, dramatically increasing people’s sense of shared awareness about themselves as a system.” “As a system…” in other words as a complex network of agents, activities and architectures that are in fact the substrates of production and creativity.

By increasing the density and the quality of relationships, SK also develops better adaptability and responsiveness. The strategic shift here is toward resilience as a driver of delivery. Borrowing the syntax from the Agile Manifesto, we could say “discovery and tuning into where we have a higher capacity to respond to the world around us as it changes” over process and planning.

Secondly, if SK does not directly address how decisions are made or how resources are allocated, that does mean that we are left bereft of solutions. There are several ways to deal with this. Within the LS tool box one could, at the end of the process, add some form of project management using Purpose to Practice (P2P) or, if looking for engagement and commitment, something around What I Need From You (WINFY).

So what makes SK so incredibly useful?

For Fisher the value of SK is not so much the answers given at any one moment of time to the 6 questions as it is to help us ““understand the relationship of one’s work to other people’s work or one’s work to the constituencies we are working for” to quote Nancy.

Looking at SK this way induced Fisher to become less formal and to use the 6 questions more like a “set of improvisational lenses” than steps in a process. Musing on the last 9 months, he acknowledges that notwithstanding intense preparation, things never followed the intended path with the business school. One reason is that perception varies within the ranks of an organization, and so you work out a detailed agenda with one constituency only to find out that it does not apply to another.

In this context, the robustness of the process is provided by the quality of the conversations, hence the importance of questions. What is really useful becomes a good library of prompts from which one can retrieve the right trigger at any moment anywhere in the process. Focusing on prompts rather than steps improves the relational capabilities of the group and helps circumvent resistances.

For example “(If) this group isn’t going to tolerate talking about purpose”, Fisher says, (…) here’s two ways of inviting them to consider purpose without calling it purpose. Right? so that becomes a Conversation Cafe topic. Here’s a group arguing about their shared portfolio, but they don’t have a language of portfolios. And so we’re going to do an Ecocycle to baseline the portfolio of investments.(…) and to conclude “it just becomes a much less structured practice and much more like fluid.”

Relational coordination is the second pillar of strategy

I mentioned Fisher’s disappointment with the lack of execution that followed the 9-month work he did with the business school. And indeed, this echoes the experience of many practitioners leading to doubt SK as a full-fledged strategic tool. While we can bemoan this state of affair, things are no better with a traditional strategic plan. The difference is that their actions are undertaken – usually with great ponderousness and miscommunication – only to be found inappropriate down the line.

Listening to Fisher I came to the conclusion that there is another side to strategy than setting goals and listing actions. As it happens this is not only my opinion. Keith referred to Jody Hoffer Gittell’s research on what she also calls relational coordination and to her conclusions that indeed it impacts performance (operations). Two remarks follow from this. One is the fact that, to quote Keith, “there are not many mechanisms in lots of organizations where that stuff is built into the fabric.” Second, this aspect of strategy cannot be top-down which may explain its absence in most companies. The reason it cannot be a top down affair is that relational coordination does not fit hierarchical models, it feeds on networks.

Of course Jody Hoffer Gittell’s attributes of relational coordination are not identical to the 6 questions of SK. Hers are: mutual respect, shared goals, shared knowledge, as well as frequent, timely and accurate communication but it is hard not to see that SK definitely addresses all of them in one form or another.