Ready for a thinking ramble? Payoff isn’t until the end. Fair warning!

Ready for a thinking ramble? Payoff isn’t until the end. Fair warning!

I have found myself pointing to Donella Meadows’ “Leverage Places: Where to Intervene in a System” more and more these days. First surfaced in the Whole Earth Catalog in 1997, and expanded in 1999, the essay resonated with me then and continues today. Read the whole thing, but if you just want to scan the leverage points, check out the Wikipedia article. When I mention the article, everyone starts pulling out their pens, phones or electronic note taking devices. People are hungry for clues about where to intervene in the complex systems within which they work and live. Here are her leverage points:

PLACES TO INTERVENE IN A SYSTEM (in increasing order of effectiveness)

9. Constants, parameters, numbers (subsidies, taxes, standards).

8. Regulating negative feedback loops.

7. Driving positive feedback loops.

6. Material flows and nodes of material intersection.

5. Information flows.

4. The rules of the system (incentives, punishments, constraints).

3. The distribution of power over the rules of the system.

2. The goals of the system.

1. The mindset or paradigm out of which the system — its goals, power structure, rules, its culture — arises.

Her number one leverage place: 1. The power to transcend paradigms. From the Wikipedia article:

Transcending paradigms may go beyond challenging fundamental assumptions, into the realm of changing the values and priorities that lead to the assumptions, and being able to choose among value sets at will.

Many today see Nature as a stock of resources to be converted to human purpose. Many Native Americans see Nature as a living god, to be loved, worshipped, and lived with. These views are incompatible, but perhaps another viewpoint could incorporate them both, along with others.

A bit more from Meadows’ essay on #1 and worth savoring, slowly:

There is yet one leverage point that is even higher than changing a paradigm. That is to keep oneself unattached in the arena of paradigms, to stay flexible, to realize that NO paradigm is “true,” that every one, including the one that sweetly shapes your own worldview, is a tremendously limited understanding of an immense and amazing universe that is far beyond human comprehension. It is to “get” at a gut level the paradigm that there are paradigms, and to see that that itself is a paradigm, and to regard that whole realization as devastatingly funny. It is to let go into Not Knowing, into what the Buddhists call enlightenment.

People who cling to paradigms (which means just about all of us) take one look at the spacious possibility that everything they think is guaranteed to be nonsense and pedal rapidly in the opposite direction. Surely there is no power, no control, no understanding, not even a reason for being, much less acting, in the notion or experience that there is no certainty in any worldview. But, in fact, everyone who has managed to entertain that idea, for a moment or for a lifetime, has found it to be the basis for radical empowerment. If no paradigm is right, you can choose whatever one will help to achieve your purpose. If you have no idea where to get a purpose, you can listen to the universe (or put in the name of your favorite deity here) and do his, her, its will, which is probably a lot better informed than your will.

It is in this space of mastery over paradigms that people throw off addictions, live in constant joy, bring down empires, get locked up or burned at the stake or crucified or shot, and have impacts that last for millennia.

Hold that thought for a moment.

A while back I happened on The Tragedy of the Commons: How Elinor Ostrom Solved One of Life’s Greatest Dilemmas – Evonomics, and another in the Atlantic about US post election responses, both of which resonated with my reading of Meadow’s essay. First, the snippet about Ostrom (another one of my compass points, like Meadows!)

“Evolutionary theory’s individualistic turn coincided with individualistic turns in other areas of thought. Economics in the postwar decades was dominated by rational choice theory, which used individual self-interest as a grand explanatory principle. The social sciences were dominated by a position known as methodological individualism, which treated all social phenomena as reducible to individual-level phenomena, as if groups were not legitimate units of analysis in their own right (Campbell 1990). And UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher became notorious for saying during a speech in 1987 that “there is no such thing as society; only individuals and families.” It was as if the entire culture had become individualistic and the formal scientific theories were obediently following suit.

Unbeknownst to me, another heretic named Elinor Ostrom was also challenging the received wisdom in her field of political science. Starting with her thesis research on how a group of stakeholders in southern California cobbled together a system for managing their water table, and culminating in her worldwide study of common-pool resource (CPR) groups, the message of her work was that groups are capable of avoiding the tragedy of the commons without requiring top-down regulation, at least if certain conditions are met (Ostrom 1990, 2010). She summarized the conditions in the form of eight core design principles: 1) Clearly defined boundaries; 2) Proportional equivalence between benefits and costs; 3) Collective choice arrangements; 4) Monitoring; 5) Graduated sanctions; 6) Fast and fair conflict resolution; 7) Local autonomy; 8) Appropriate relations with other tiers of rule-making authority (polycentric governance). This work was so groundbreaking that Ostrom was awarded the Nobel Prize in economics in 2009.”

Notice Ostrom’s core design principles. See any relation to Meadows’ leverage points?

Now switch to the Atlantic article titled “Americans Don’t Need Reconciliation—They Need to Get Better at Arguing” by Eri Liu. Commenting on the need for work in the social sphere following our divisive presidential election, Liu suggested we needed three things:

- Listen more to each other (in listening circles”)

- Work more together (national service)

- Argue more. But do it well (“We don’t need fewer arguments today; we need less stupid ones.”)

Liu gives us three concrete ways of unlocking the patterns and leverage points.

My work has clearly been situated in ever increasing turbulence. Traditional strategic planning? Throw it out the window. Focusing on mission and vision? Unless tied to concrete, actionable purpose, throw it out the window. It is too easy to be lost in our own abstractions and old/stale paradigms. (Thank you Donella!) Building knowledge management systems to capture everything? Fuggedabout it if we aren’t listening to each other (Thank you, Eric!) Trying to work just top down and with existing, rigid governance systems? Do you have all the time in the world? NO, ditch it! (Thank you, Elinor!)

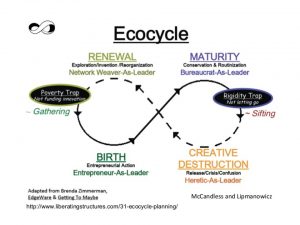

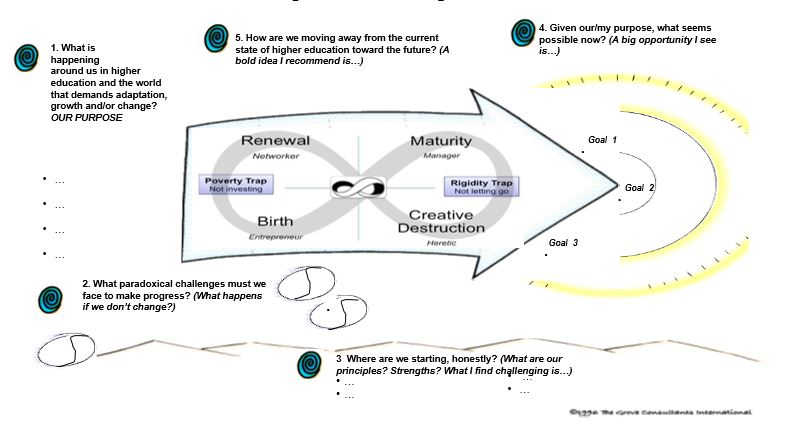

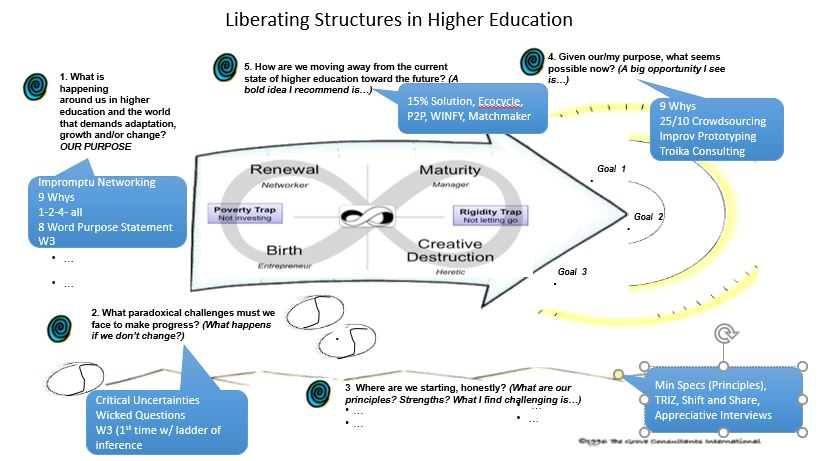

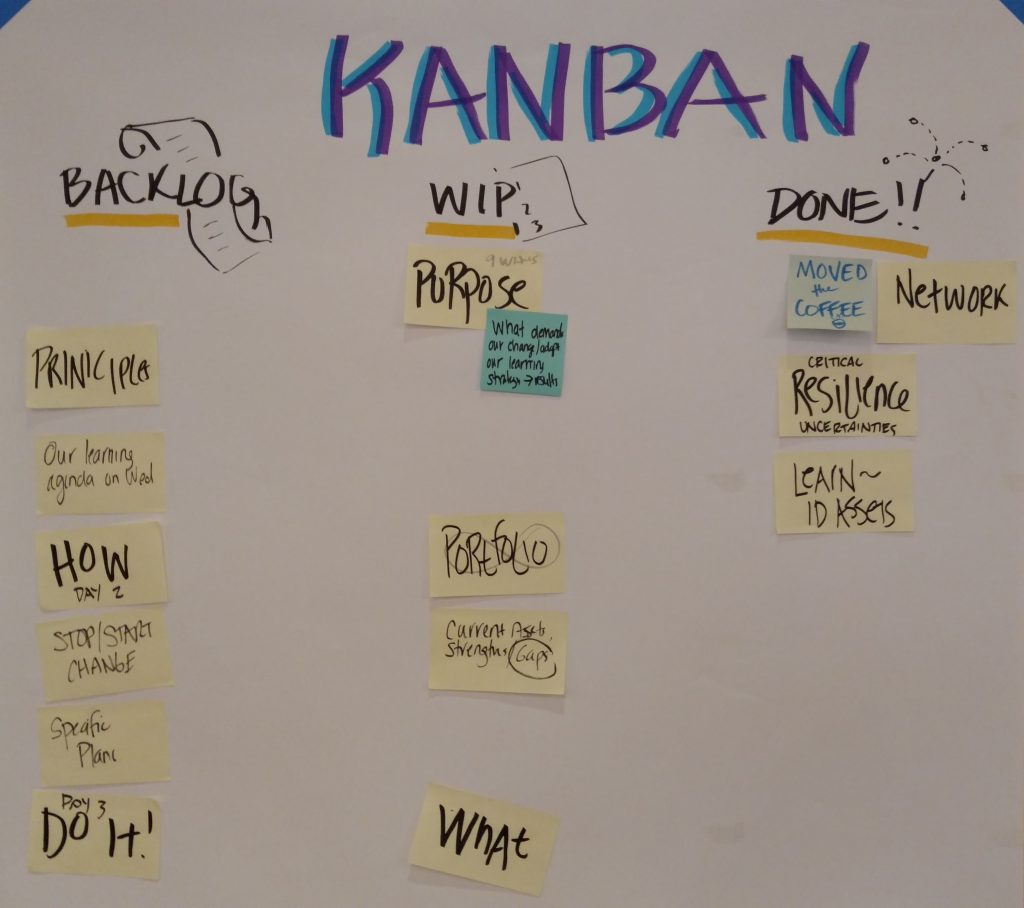

So how am I designing now? Quickly, iteratively, and ruthlessly reflective. My group process practices in the last 18 months reveal a pattern where groups are getting more traction into creating insights on their work, and slightly increased traction on acting on those insights. I attribute this two two things: the application of Liberating Structures and other group processes that are informed by complexity sciences, and the use of emergent visuals to help show the path of thinking, understanding and action. The processes devolve power and responsibility to, as LS says, “unleash and include” everyone. They focus on immediate steps rather than waiting for certainty and perfection. They ask us to question our assumptions, measure our experiments and understand negative and positive feedback loops (Meadows again!) They seek to sidestep the barriers of traditional governance as much as possible without rejecting the participation of those institutions.

So how am I designing now? Quickly, iteratively, and ruthlessly reflective. My group process practices in the last 18 months reveal a pattern where groups are getting more traction into creating insights on their work, and slightly increased traction on acting on those insights. I attribute this two two things: the application of Liberating Structures and other group processes that are informed by complexity sciences, and the use of emergent visuals to help show the path of thinking, understanding and action. The processes devolve power and responsibility to, as LS says, “unleash and include” everyone. They focus on immediate steps rather than waiting for certainty and perfection. They ask us to question our assumptions, measure our experiments and understand negative and positive feedback loops (Meadows again!) They seek to sidestep the barriers of traditional governance as much as possible without rejecting the participation of those institutions.

People get it. Quickly. The visual practices help bookmark the moments of insight and support telling the story to others.

The traction for action is still a bit elusive. Our reward systems punish many of the behaviors of emergent practices. Power is challenged. And just getting a grip on all the working parts can serve as an excuse to throw one’s arms up and give up. But we won’t give up. Nope. Sadly, Meadows and Ostrom died too young. But their words continue to feed us.

Stay tuned. Share your thoughts!

Edit: See this great post by Chris Corrigan on Prototyping and Strategic Planning. I had THOUGHT I had linked it in, but clearly that was in my dreams! Dave Pollard also recommends the work of Nora Bateson.

When approached to support knowledge management (KM) in my consulting practice, I often reply “I don’t believe in KM!” This flippant but heartfelt comment reflects the failures I’ve observed as people tried to reduce the complex processes of learning, creating, sharing and applying knowledge into a set of “best practices” and databases. It was as if KM was a mechanical but glorified tool, like a fancy food processor, admired while new, and then left on the shelf. Most KM approaches failed to understand that at the heart of creating, sharing, adapting knowledge is embedded in our entrained human behaviors and rarely successfully redirected by rules. Especially for busy people. Yes, I am a skeptic of of many KM approaches.

When approached to support knowledge management (KM) in my consulting practice, I often reply “I don’t believe in KM!” This flippant but heartfelt comment reflects the failures I’ve observed as people tried to reduce the complex processes of learning, creating, sharing and applying knowledge into a set of “best practices” and databases. It was as if KM was a mechanical but glorified tool, like a fancy food processor, admired while new, and then left on the shelf. Most KM approaches failed to understand that at the heart of creating, sharing, adapting knowledge is embedded in our entrained human behaviors and rarely successfully redirected by rules. Especially for busy people. Yes, I am a skeptic of of many KM approaches.