A guest post by Philip Clark

Introduction: I am happy to share the blog space with guest author Philip Clark for the fourth in the series of his reflecting on the learnings of our little CoP on strategy knotworking. You can read his bio at the end of the post!

“Where passion meets precision, mastery is born.” – Bruce Lee

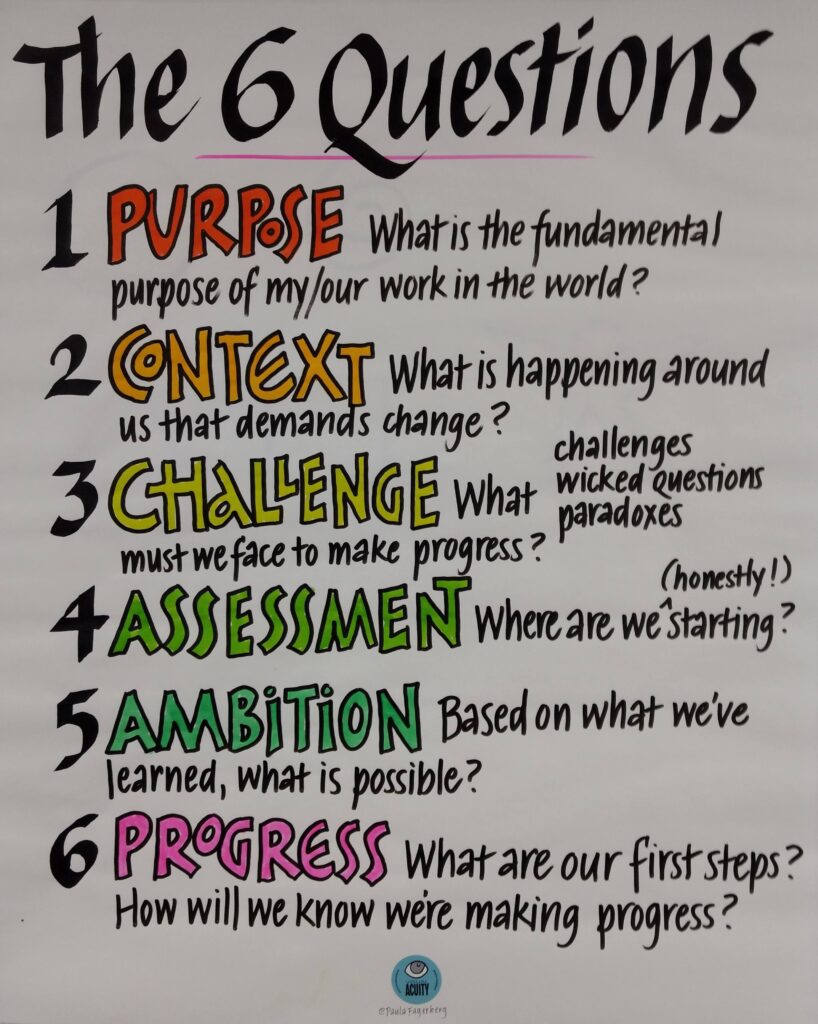

Within the larger Liberating Structures network there is a community of practice devoted to the development and understanding of Strategy Knotworking (SK), a set of six questions, often answered using various Liberating Structures (LS). SK lends itself to complex contexts and where there is a desire to engage everyone in planning.

This is the fourth installment (here is the first, here is the second, here is the third) of takeaways from the various conversations that we have been fortunate to have with seasoned practitioners on Strategic Knotworking (SK). Today, the guest is Barry Overeem.

Barry is one of the two founders of TheLiberators. The other is Christiaan Verwijs. To say they’ve been instrumental in the diffusion of LS across Europe would be an understatement. Not only are they consummate facilitators, but they’ve also produced one of the most extensive bodies of literature on Liberating Structures in Europe, built an impressive community around their work and LS, and, last but not least, created one of the sleekest, coolest pop-style brand identities. Nancy calls them “real super spreaders” and “generous,” while Keith praises Barry’s “liberating superpowers.”

Their output is prolific (articles, podcasts, visual artifacts, surveys, workshops, tools, meet-ups, posters, academic research) and what is truly remarkable about this flurry of activities is that most of it is absolutely FREE for anyone who cares to look, think and be curious about LS in general and its interaction with Scrum in particular.

Barry discovered LS in 2018 starting a lifelong affair. From then on he says, “I used Liberating Structures for my training, workshops, and meetups. More importantly, I also use it for regular day-to-day conversations and meetings.” For Barry, the ultimate value of LS is to make things actionable. They are fast, easy to use, and provide the right balance between structure and creativity.

Barry’s interview offers a wealth of insights. You can listen to the recording here : https://fathom.video/share/5Q6Fb58cc5djdrzkr_-vdPJNdqCKeKKG

Here are 3 takeaways:

- Strategic execution will be improved if you think of strategy as a narrative

- SK is amenable to many usages

- SK welcomes process innovation and new tools

Strategic execution will be improved if you think of strategy as a narrative

Execution is the Achilles’ heel of strategic knowledge. The critical question is: how do we ensure insights from workshops translate into lasting, sticky outcomes?”

The traditional solution is action plans. But the truth is, they rarely work as intended. When treated as the ultimate path to implementation, they often prove unsustainable, leading to defunding, abandonment, or waste. Is there a better alternative? More precisely, a more sustainable, antifragile, and “sticky” way to ensure that the insights and foresights gained in SK actually take hold?

Barry believes that the true power of SK doesn’t lie merely in drawing up a plan—or in sense-making terms, sensing, ordering, and acting—but in crafting a compelling narrative. Even the most streamlined action plan cannot, on its own, guarantee the successful delivery of strategy. A shared storyline that people can own and engage with, however, can.

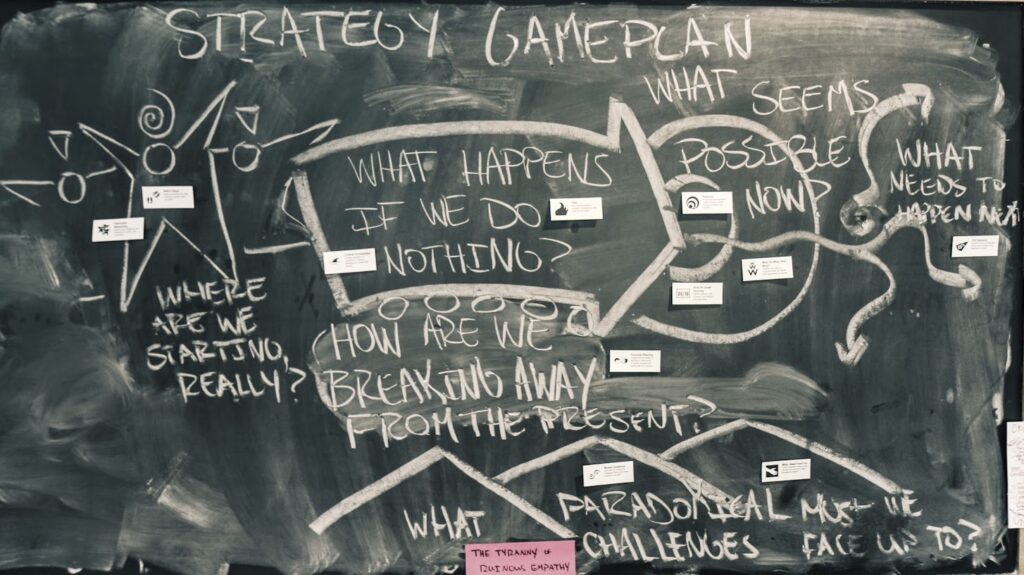

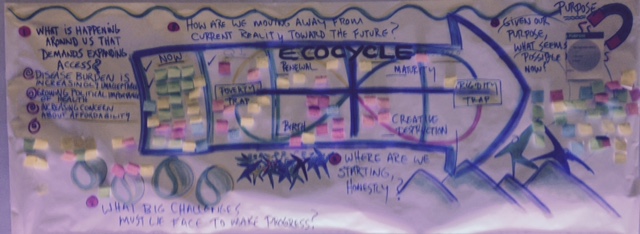

Barry emphasizes that when a narrative is clear, inspiring, and meaningful, people are far more likely to act on its outcomes. To help teams develop their strategic narrative, he employs visual tools like posters and whiteboards and encourages them to continually revisit key questions, ensuring the narrative evolves and remains relevant.

SK is amenable to many usages

SK is, first and foremost, a strategic tool—a framework designed for crafting strategy. However, the Liberators uncovered another powerful application: using it as a platform to teach and train people in LS.

Once upon a time, TheLiberators were well known throughout the LS community for their LS Immersion Workshop (Barry recently announced that he’ll no longer be offering this workshop to the public), where large groups of participants were invited to discover, explore, and experiment with roughly 20 LS from the original repertoire. The 2-day workshop was an immediate hit drawing large crowds and sparking numerous vocations. Yet, this approach left a significant portion of LS unexplored.

It soon became clear that a sequel was needed for participants to fully integrate LS into their toolbox. In response, The Liberators introduced a second, more advanced—though Barry dislikes the term—workshop, designed to deepen participants’ fluency by exploring and testing more complex LS, such as Panarchy, What I Need From You (WINFY), and Drawing Together. And the perfect vehicle for this next step? SK—providing a clear framework to guide and elevate the entire journey.

In complexity, the only certainty is that every action brings unintended consequences. Such was the case when Barry found himself facilitating an “advanced” workshop for the Dutch Ministry of Defence, intended to build on their existing knowledge and skills in LS. However, an hour into the session, the participants found the framework so powerful and compelling that they decided to test it as a strategic tool on their own organization—completely shifting focus from the original purpose. And so, SK, which had evolved from a strategy tool into a support for training, came full circle—once again being used to shape strategy.

SK welcomes process innovation and new tools

SK follows a certain sequence, and Barry has experimented with different combinations, but he typically ends up with Purpose, Baseline, Context, Challenges, Ambition, and finally Action and Evaluation. To him, this progression seems both logical and helpful in keeping groups focused on the realities of their current situation.

This reason is straightforward: it helps participants enter the strategic process—often daunting—through something familiar. Another way to say this, Barry suggests, is to look at SK through the lens of W3 (What? So what? Now what?). From this perspective, Baseline represents the ‘what’—the concrete reality of one’s work. From there, participants explore the ‘so what’ by assessing context and challenges, leading to the ‘now what’ as ambitions and actions take shape.

But the true shift brought by The Liberators is cognitive.

Their mission statement (“to unleash teams all over the world from outdated, old-fashioned, and ineffective ways of working through an evidence-based approach.”) focuses on an “evidence-based approach”, moving away from subjective assumptions towards data-driven analysis. This approach is built on Christiaan’s research (https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3571849 )at Aalborg University with Daniel Russo, which pinpoints the key factors that affect team performance. The result is Columinity—a tool that gives teams a clear picture of their strengths and weaknesses and how to address them. Teams can compare their results either with other teams in their organization (if multiple teams are involved) or against a broader benchmark from the entire study. (A good place to start learning about Columinity is here: https://medium.com/the-liberators/study-the-underlying-research-of-columinity-and-set-a-solid-foundation-to-get-started-d44dc168fce4 )

Readers of earlier blogs may recall that Lynda suggested examining context through the lens of comparative advantages rather than external triggers for change. Both Lynda’s and Barry’s value proposition could be summed up as follows: grounding your inquiry in existing capabilities clarifies options and prioritizes execution.

There is much to explore about Columinity and its integration with SK, particularly its impact on the remaining steps of the strategic process. But that’s a discussion for another time.

Conclusion

Reflecting on SK as a process, two key insights from TheLiberators stand out: its interpretation as a narrative and its potential for adaptability

The first lesson is to view SK not only as a process, but as a narrative. This was, and to a large extent still is, new to me. However, I’ve come to realize that thinking of strategy this way is incredibly useful—not only to make sense of our reality (as humans, we are natural storytellers) but also to enhance the flexibility of strategy. Narratives give skin to the bones of process, or, to put it differently, they add feeling and emotion to logic.

The second lesson is how SK is exceptionally adaptable. We also saw this inclination toward accommodation with Lynda and Michele. Lynda not only redefined the question of context but also integrated frameworks and tools from other approaches to strengthen execution. Michele introduced an alternative way of exploring context through the history of organizations. As for Barry, not only did he tweak the sequence of SK’s steps to secure stronger participant buy-in, but he also introduced a completely new tool —reshaping the very definition of Baseline.

Finally, looking at the way TheLiberators work, I’m struck by how deeply aligned they are with the spirit of LS. As far as I know, the scope and depth of their work with LS is unmatched in Europe— and freely available to anyone interested. It’s a treasure trove of insights, ready to be explored and learned from. I encourage everyone to take advantage of it.

Strategy isn’t within everyone’s reach—it’s often reserved for a select few somewhere between heaven and earth. But SK’s modularity makes it accessible at any level of your organization. A sense of strategy—call it a direction of travel if you prefer—is valuable no matter who you are or what you do. And SK puts it within everyone’s grasp. You don’t have to follow the whole process—use what you need, when you need it. In doing so, you’ll not only gain a deeper understanding of your activities but also develop the skills to facilitate many LS.

Our Guest Author

Philip Clark:. After running his company -a digital design firm – for 10 years, and the innovation department of Orange Business Services, Philip now teaches innovation and change at the university of Applied Science in Lausanne Switzerland. He also facilitates organizational transformation with a special emphasis on complexity designed tools and methods (Liberating Structures, Cynefin, Estuarine, Sensemaker…) promoting collective intelligence and distributed leadership. Contact Philip to collaborate and share ideas (https://www.linkedin.com/in/philip-evans-clark/)