Are you at or near the University of Illinois at Champagne/Urbana? Interested in Liberating Structures? Then join us for one or two days of hands/heads/hearts on workshops. The first one is a new offering I’ve put together that builds on some of my recent blog posts (and more to come) about facilitating in complex contexts!

Are you at or near the University of Illinois at Champagne/Urbana? Interested in Liberating Structures? Then join us for one or two days of hands/heads/hearts on workshops. The first one is a new offering I’ve put together that builds on some of my recent blog posts (and more to come) about facilitating in complex contexts!

April 5 Learning the Strategy Game Plan: Liberating Structures for Development

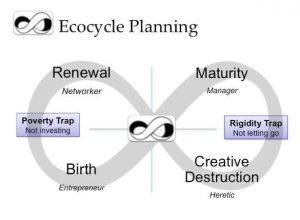

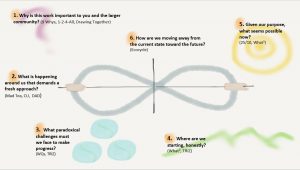

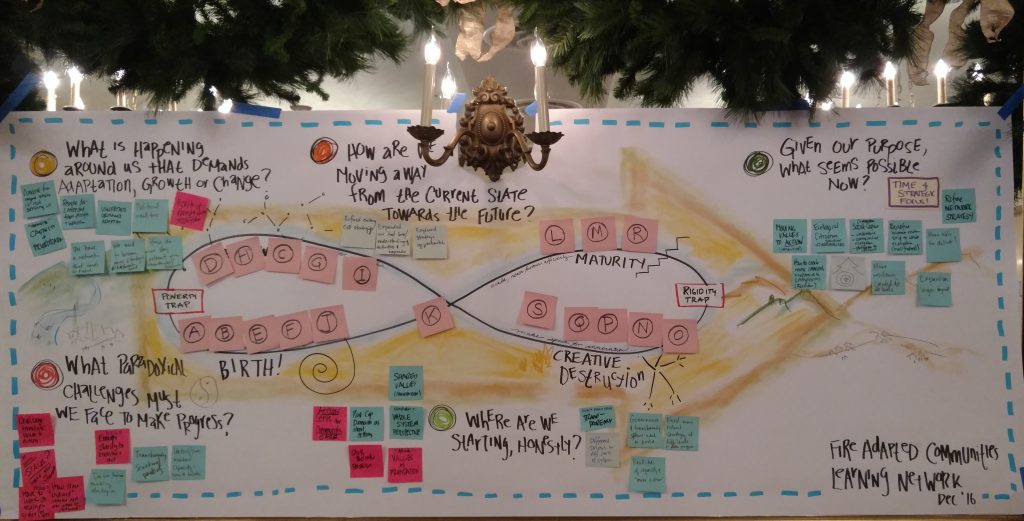

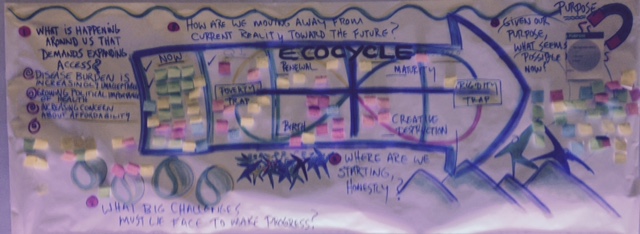

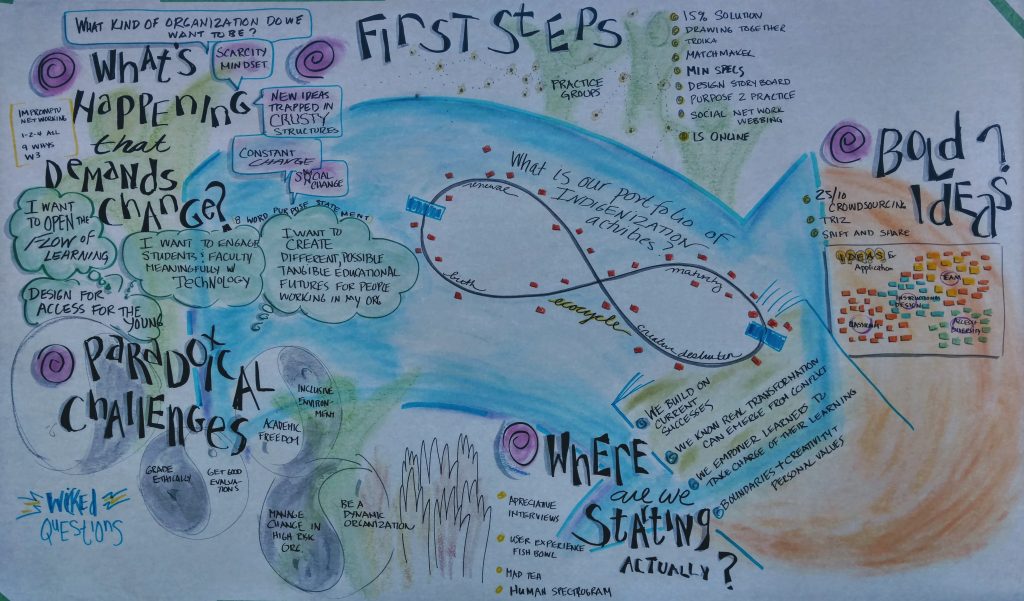

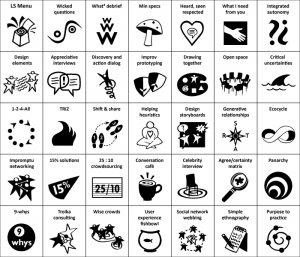

The first workshop is on April 5th, 8:30 am – 5:30 pm. It is designed to explore how we can use Liberating Structures, a repertoire of 33 group practices, to improve project planning and execution for participatory projects that are often on complex and emergent contexts. While a funder or boss may want a linear log-frame and a budget, we need to find approaches that embrace ambiguity with practical approaches, ensure learning and improvement are part of the design, not an afterthought, and which consistently liberate and unleash the knowledge and experiences across the system at play.

In the workshop you will practice 6-8 structures and utilize an overarching framework to tie the pieces together in a cogent, visual whole. The fee is $100.00, registration is here, and a brief flyer is attached to this blog post. Leave me a comment with any questions. Spread the word!

April 6th, Unleashing Learning Engagement in the Classroom

The second is a series of three, 90 minute workshops that dive increasingly deeper into the use of Liberating Structures for increasing classroom engagement in higher education. We’ve designed this with the busy professor/lecturer/Graduate Student/TA in mind.

Is it a challenge to engage all student voices in your classes? Do you look for ways to spark deeper student engagement the subject matter and with each other? Do you wish they would take more ownership and risks in their learning? Engagement deepens learning and application. It strengthens the muscles that help students work with ambiguity. But it can be challenging, in both small and large groups.

Come explore Liberating Structures, an easy to learn and deploy repertoire of of 33+ open source interaction structures that can build patterns of easy, regular student engagement in the classroom. They quickly foster lively participation in groups of any size, making it possible to truly include and unleash everyone.

You can start with a short 90 minute introductory workshop, or stay for all three learning sessions. First is an introduction of the easiest and most often used Liberating Structures, second, a focused application to solve a real challenge, and third, a deeper dive into the theory and practice behind Liberating Structures.

8:30 – 10:00 Workshop 1: Liberating Engaged Learning: discover and use 4 structures that can immediately increase engagement in your classroom.

Friday, April 6, 2018 Illini Union Ballroom

8:30 am to 10:00 am Workshop 1: Liberating Engaged Learning: discover and use 4 structures that can immediately increase engagement in your classroom. In this 90 minute session you will get a hands on introduction to some of the easiest and most commonly used Liberating Structures to build student engagement in your class. It will conclude with a debrief and identification of immediate applications in your classroom. You can then build your practice by turning to the instructions for individual structures on the website (www.liberatingstructures.com), mobile phone app (available free on iTunes and Google Play) or continue with the two following workshops.

10:30 am to 12:00 pm Workshop 2: Stringing Structures to Tackle a Challenge in Your Classroom: learn how a sequence of multiple structures can address specific challenges (student, passivity, unequal participation, lack of critical thinking, etc.) and larger outcomes. This builds on Workshop 1.

Liberating structures can be used individually, but their power becomes more visible when they are joined together or “strung.” In this 90 minute session we will use a string of 2-3 Liberating Structures to collaboratively work on addressing a concrete shared classroom challenge such as how to create an open environment and tackle a lack of student participation, end student passivity, weak discussions, or the lack of productive risk-taking. You will walk away with at least one actionable solution you can apply the next time you are in the classroom. You will learn how to use the Liberating Structures Matchmaker tool to select and string the structures. Prerequisite: Workshop 1

12:00 pm to 1:00 pm Lunch Break (grab lunch in the food court or on Green Street) with someone you just met this morning

1:00 pm to 2:30 pm Workshop 3: Understanding the Theory Behind Liberating Structures: an advanced workshop that looks at the underlying elements of Liberating Structures and how they can become part of the everyday pattern of highly engaged classrooms. Liberating Structures can appear to simply be “yet another facilitation tool.” What sets them apart is the attention to five microstructures that sit beneath each Liberating Structures, and the ten principles that guide them. These give us insight as to how and why Liberating Structures work well for stronger classroom engagement, enable more critical thinking, innovation and action. In this workshop we will explore some of the theory behind Liberating Structures and experience a few of the more complex and rich structures. You will also be introduced to various vectors for continuing to learn and practice Liberating Structures. Prerequisite: Workshop 1 and/or 2.

It’s worth your time to come to all three, but if you can only attend one, then come to the first. If you can do two, then combine workshops 1 and 2 or workshops 1 and 3.

Registration is here and the short flyer is attached below.

Flyer – LS Workshop on April 5 2018 – Strategy Game Plan

Flyer – LS Workshop on April 6 2018 – Unleashing Learning Engagement – external