This is the third of a series of posts to support anyone working to move their offline/face to face group interactions online. It is pretty “drafty” and hopefully there will be energy to improve.

The preamble is here and Part 2: Ecocycle here. If you are an online facilitator or finding yourself in that role, join our group here. If you are looking for resources, check here.

In the race to do SOMETHING as we are forced to move many group interactions online, there is something we MUST NOT DO. That is replicate terrible offline meeting habits online. They only get worse. If it was bad F2F, you will have total turn off and rebellion online.

So the first step is to figure out what to STOP doing, before you make a list of all the things you are GOING to do. There is a fantastic Liberating Structure called TRIZ, which works really well online (as well as offline!) Here is the intro from the Liberating Structures website.

Making Space with TRIZ* – Stop Counterproductive Activities and Behaviors to Make Space for Innovation

http://www.liberatingstructures.com/6-making-space-with-triz/

Every act of creation is first an act of destruction. – Pablo Picasso

What is made possible? You can clear space for innovation by helping a group let go of what it knows (but rarely admits) limits its success and by inviting creative destruction. TRIZ makes it possible to challenge sacred cows safely and encourages heretical thinking. The question “What must we stop doing to make progress on our deepest purpose?” induces seriously fun yet very courageous conversations. Since laughter often erupts, issues that are otherwise taboo get a chance to be aired and confronted. With creative destruction come opportunities for renewal as local action and innovation rush in to fill the vacuum. Whoosh!

* Inspired by one small element of the eponymous Russian engineering approach teoriya resheniya izobretatelskikh zadatch.

This post will take you through step by step doing TRIZ online, supported by slides on Google Drive. Here is the visual on the LS site that gives a great quick gist of the process.

I’m assuming you typically get your team together in your video conferencing space. Ideally you are using a tool that allows breakout groups like Zoom. (Pssst, someone told me today that breakouts are possible on Microsoft Teams. If you have instructions, leave a comment!)

The preparation:

- Prepare a Google Doc, Slides (one slide per group) or something similar for each breakout group. Set the permissions so everyone can edit. Have the urls handy to paste into the chat room at the appropriate moment.

- Have the step wise instructions ready to copy/paste into the chat room. One instruction – they go do it – then the next. Don’t put them all in at once.

- Refine your invitation. The one below is for specifically stopping bad meeting habits before they go online, but you have many options!

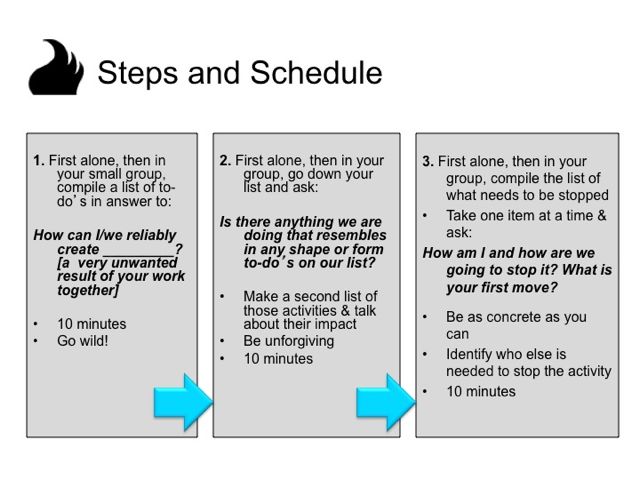

The invitation: In plenary in your online meeting space welcome folks and then dig in. “First alone, think about how we could reliably design our online meeting so that nothing got done, everyone had a TERRIBLE time and our leadership and credibility is seriously damaged. Make a list of all the things you would have to do to make this happen. Go wild! I’ll post this instruction in the chat to keep it top of mind.” Paste these first instruction in chat. While people are thinking alone, prepare your breakout groups. 2 minutes

In your group: In a moment tell folks you are going to put them into breakout groups (If you need to, describe how that works on your platform!) In chat paste the next step instruction, and then the urls for each breakout group Google Doc – so doc #1 goes to breakout group #1. Sometimes people get confused. If they all end up in the same google doc, that is ok. They can figure it out!! Here is their task: “In your group, share your ideas and compile a master list in your Google Doc. You have five minutes then I’ll pull you back into the ain room for a touch point. In the template I’ve drafted, you can do the lists right into the Google Slides too! Make a separate slide for each group. 5 minutes

Touch point: At this point you can quickly bring everyone back to briefly check in and set up the next step. “Have you created the design for absolute failure? Give me a few examples of the most horrendous things you can do.” This gets people riled up even more!

Next Step: What is real? Tell them you are going to send them back into their groups. “Now run through each element. Which of these elements is currently present in your work practices. Highlight those in your Google doc. Calculate what percentage you are actually DOING? You have five minutes then we’ll come back for a touch point. Paste in this instruction then send them on their way!

Touch point: Quickly ask what percentage are highlighted. This is where it gets real, my friends!

Next Step: Tell folks you are going to send them to breakouts one more time. “Next pick one or more of those things to STOP doing before you design your online meetings. What is the first step you need to do to STOP it? Make a plan to do that. Be as concrete as you can and identify who has to be involved to make it happen. Be prepared to share your next steps when we return to plenary. You have 10 minutes. Paste in this instruction then send them on their way!

When everyone is back, prioritize your collective next steps to STOP doing. Then reflect on the process. What is liberated when we identify what to STOP doing? What is made possible?

Riffs, Variations and Hacks:

There are some hacks here, too. The timing may vary, don’t go too slow. People can start turning into a complaint session and that is not the intention. If your group is small, keep them all in the main video conferencing room. If you are in a tool like Zoom where you can send messages to the breakout rooms, you can help them keep track of time.

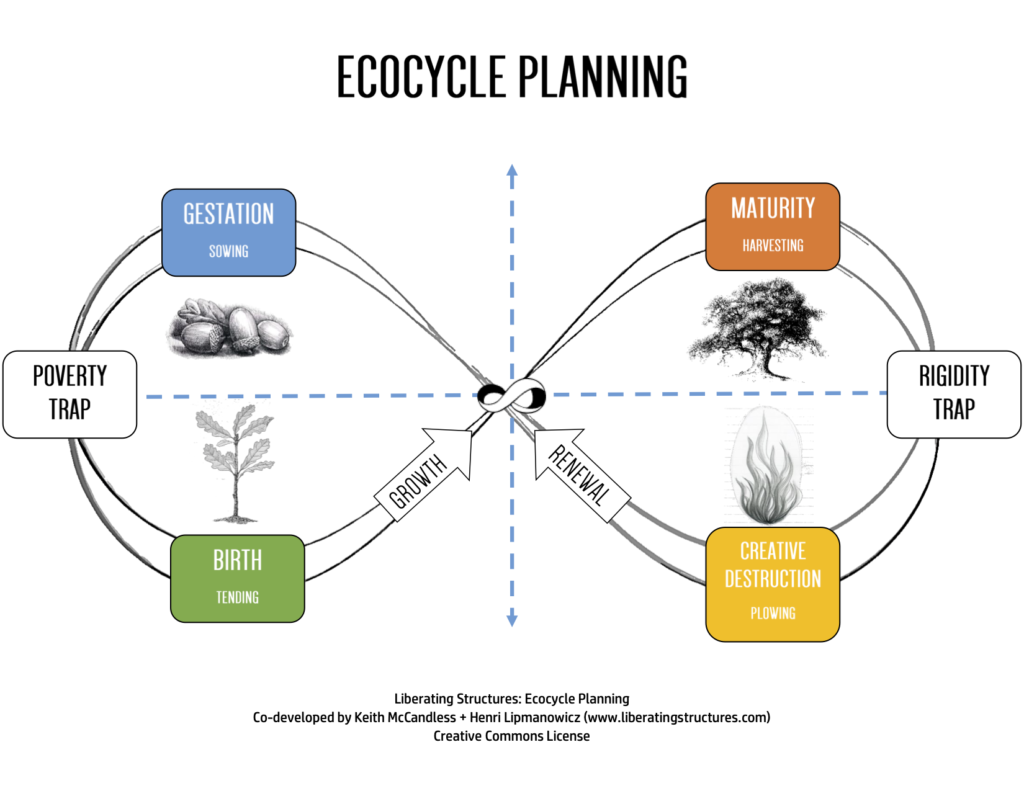

In the second post of this series I wrote about Ecocycle. TRIZ is great to move past being stuck in the “rigidity trap” in the Ecocycle, and into creative destruction. It is great to help people get out of their individual and collective ruts. The example here is focused on stopping bad meetings, but your invitation can be anything that needs a little creative destruction!!

Thoughts? Feedback?