In this season of immense natural disasters around the world (fires, floods, earthquakes, hurricanes, war, famine, drought…) and here in the northern hemisphere, with a shift in the seasons themselves, I woke up thinking about transitions, and how we use them as plumbers and poets.

In this season of immense natural disasters around the world (fires, floods, earthquakes, hurricanes, war, famine, drought…) and here in the northern hemisphere, with a shift in the seasons themselves, I woke up thinking about transitions, and how we use them as plumbers and poets.

As a group process facilitator and change agent (or as Keith McCandless says, a “structured improvisationalist!), transitions are where real progress or failure happens. They are the moments when more is possible – often much more than we ever imagined. Disasters are transitions at a grand scale. Moments in a meeting are often at a subtle and even unnoticed scale. Both can and do change our future trajectories.

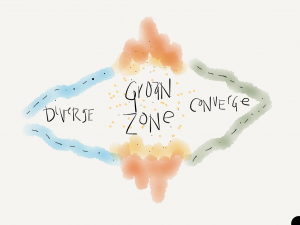

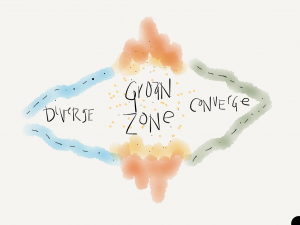

Transitions are often messy. Sam Kaner and his colleagues coined the term, “the groan zone” to describe a critical transition in group process. It is part of his larger “diamond of participation” from the “Facilitators Guide to Participatory Decision Makers,” an essential facilitation tome.

Transitions are often messy. Sam Kaner and his colleagues coined the term, “the groan zone” to describe a critical transition in group process. It is part of his larger “diamond of participation” from the “Facilitators Guide to Participatory Decision Makers,” an essential facilitation tome.

The groan zone is the transition from the opening, divergent part of group process to the convergent, decision making and acting part of the process. Think about the energy of ideation at the start of a project where people are flourishing in possibility (or not!). Then reality comes — we move into decision making and, hopefully, action. In this liminal space we are often uncertain, confused, and lack confidence or momentum. Intellectually and viscerally the groan zone concept and its expression in my work has always resonated for me. It named a transition that is critical for groups to move forward.

The wisest piece of advice from Kaner’s book was to name this discomfort and use it. I use that advice daily. But there is more to the practice than acknowledging discomfort. I want to reflect on both the intellectual and visceral, or intuitive aspects of this practice of working with transitions, especially groan zones.

This is where the plumbers and poets reference in the title comes in. Stephanie West Allen is a colleague who is constantly spotting and sharing resources. when the poets and plumbers link passed across my screen I paused. YES. Here is the quote from James March that Dale Biron shared in his blog post:

There are two essential dimensions of leadership: “plumbing,” i.e., the capacity to apply known techniques effectively, and “poetry,” which draws on a leader’s great actions and identity and pushes him or her to explore unexpected avenues, discover interesting meanings, and approach life with enthusiasm. ––James March, Stanford Professor Emeritus

(I am looking for the original source. I think it is from “On Leadership” by James March and Theirry Weil)

The metaphor applies far beyond leadership roles. Here I explore it from the facilitator process, but think about it for leaders, for followers, for disruptors and peace makers.

The facilitator as “plumber” comes prepared with intellectual knowledge of how humans operate socially, and the context for their work. This is a great place for the application of complexity theory, such as Brenda Zimmerman and Dave Snowden’s work, along with a sorts of socio/relational frameworks. This is often linked to theory, but I recognize some start with theory to build their approach, and others end with it to understand their work.

The groan zone is also an essential space for understanding and using differing views, contradicting view points and embracing diverse possibilities. Dave recently wrote about this and one snippet from the post offers a good taste:

The use of parallel safe-to-fail experiments over short timescales based on differing and ideally contradictory hypotheses about what is happening and what is possible. But critically any such experiment, which is ’nudge’ should only be to shift things to an adjacent possible, to something sustainable at the point of intervention.

Note the words “nudge” and “shift to an adjacent possible.” This is not only experimentation to identify next steps in complex settings, but they increase the diversity and its possibility within the group process. Sound like a possible transition or “groan?” Yup. So the work of my complexity teachers is essential for the technical “plumbing” work.

Technically we come prepared for transitions with skills on how to design them to meet goals and adapt to changing circumstances. So when I design with Liberating Structures, I assemble a string of structures that support the diamond of participation, including the groan zone, with options prepared and improvised as needed. Structures that support the groan zone include TRIZ, Wicked Questions and Ecocycle, which help to unmask polarities, “elephants” in the room and dig deeper into sensitive and challenging issues, 9 Whys to explore assumptions, 15% Solutions and Troika Consulting which allows us to quickly iterate and reflect on options with peer input, Helping Heuristics for when our interpersonal dynamics are slowing progress, among many others.

That said, intellectually and technically prepared is not enough for me. I can never be a good enough plumber (technician) without the poet side of things. The poet has to be present in every meaning of the word, with senses alert, intuition as open and calm as possible. Even the stance of my body can be part of the poet. For example, when I’m sensing disruption, confusion, fear or people feeling rejected and unheard, I stand or sit as straight as I can, arms and legs uncrossed, palms forward. Deep breaths. Most often I have no intellectual idea of what I should do at this moment beyond listening and being present. As I literally shift my stance, something changes for me. My observations and intuition tell me sometimes something changes for people in the room as well. Maybe it is mirror neurons at work. We CAN be changed and influenced by what we see and perceive with our senses. Regardless, this is part of the flow of energy in group process. Can I measure this? No. Can I fully describe it in purely technical terms? No, not me. But it is inextricably linked to both self-awareness and something I find inexpressible.

Of the many masterful facilitators I learn from, the visual facilitator Kelvy Bird has most clearly articulated this presence element in her work here on scribing, and here on opening, with a clear recognition of the “social field” within which we work. (No surprise as she is a key partner in the Presencing Institute! I am waiting for her book!)

Here is an example of what Kelvy helped me see. There is a distinction of presence and openness as compared to neutrality. Neutrality used to be one of the core values of facilitators (as previously espoused by the International Association of Facilitators and others.) As I’ve gotten further in my career, I’ve felt more and more like describing my stance as neutral was not only disingenuous, but it was false. I may be a listener at one moment, a provocateur in another, and a co-creator in yet another. I am happy that the language of neutrality has been left behind with a greater emphasis on attending to influence. The latest IAF facilitator core compentencies describes this as “Vigilant to minimise influence on group outcomes,” and “Maintain an objective, non-defensive, non-judgmental stance.” This resonates with my sense of stance and presence – even while I still struggle with objectivity and our ability to always be objective! This is far from technical “plumber” work, but it is useful to observe that the best plumbers I know have “hunches” about what they can’t see behind a sealed up wall! So the plumber and poet are not two, but one.

By being part of the process, I am changing the outcome. I am not neutral and I am influencing in certain ways. While I am strict with myself to clearly call out my own opinions, “take off my facilitator hat,” I do have influence. And it is only when I’m open and clear, self-aware and fully present, that that influence can be in the service of the group and influenced by the group itself, not to my espoused beliefs and/or ego. This is most important at transitions: the start of an engagement, during the groan zones, and as we move into resolution and reflection. It is a dance between the technician and the poet, between clarity and beauty. Between words and images.

I’m not sure this all makes sense as I struggle to write about it. I guess the only way I can express it is to say the poet in me keeps evolving. Early on, I stuck to clearly proscribed forms (Limericks! Haiku!) Now my poetry is in process, words, images, and my own presence.

Let me be clear. There are many risks to this stance. If my self awareness weakens and fails, I can cause failure around me. If my openness cracks me open and I fall apart, I cannot serve. If I come without enough clarity and energy, my services suffers. This is not just a technical nor “expert” practice. It is all in. All. In. Again, from Kelvy:

We learn through copy. We advance through integration. We master by tapping into our own source.

So how does this relate to transitions? The technician, the plumber, can spot most of the the structural transitions. The poet senses the subtle ones, energy, hunches, buried treasures, that are often the ones that take us to new places, that help us make progress in complex or even chaotic contexts.

At this point in my career, I’m deeply interested in the poet. How about you?

When approached to support knowledge management (KM) in my consulting practice, I often reply “I don’t believe in KM!” This flippant but heartfelt comment reflects the failures I’ve observed as people tried to reduce the complex processes of learning, creating, sharing and applying knowledge into a set of “best practices” and databases. It was as if KM was a mechanical but glorified tool, like a fancy food processor, admired while new, and then left on the shelf. Most KM approaches failed to understand that at the heart of creating, sharing, adapting knowledge is embedded in our entrained human behaviors and rarely successfully redirected by rules. Especially for busy people. Yes, I am a skeptic of of many KM approaches.

When approached to support knowledge management (KM) in my consulting practice, I often reply “I don’t believe in KM!” This flippant but heartfelt comment reflects the failures I’ve observed as people tried to reduce the complex processes of learning, creating, sharing and applying knowledge into a set of “best practices” and databases. It was as if KM was a mechanical but glorified tool, like a fancy food processor, admired while new, and then left on the shelf. Most KM approaches failed to understand that at the heart of creating, sharing, adapting knowledge is embedded in our entrained human behaviors and rarely successfully redirected by rules. Especially for busy people. Yes, I am a skeptic of of many KM approaches.