Let me confess right up front: I really don’t like webinars. Too often they feel “done unto me.” I am powerless, at the mercy of the organizers. I may have access to a chat room (Thank Goodness!) But more often than not, these are content delivery mechanisms with token participant interaction in the form of crowded Q&A segments or polls with varying degrees of relevance. What is worse is that I have been a perpetrator of these practices so I continue to try and change my evil ways.

Let me confess right up front: I really don’t like webinars. Too often they feel “done unto me.” I am powerless, at the mercy of the organizers. I may have access to a chat room (Thank Goodness!) But more often than not, these are content delivery mechanisms with token participant interaction in the form of crowded Q&A segments or polls with varying degrees of relevance. What is worse is that I have been a perpetrator of these practices so I continue to try and change my evil ways.

Changing ingrained habits requires some reflection – of self and of the state of the practice of these so-called “webinars.” Recently I had the chance to offer feedback on a webinar I experienced as a recording. I’ve edited/generalized my thoughts to share. In a follow up post I’ll reflect on my own practice — this is where I need to cut to the bone!

1. Us/Them: It is logical for an organizer or organizing agency to want to appear well prepared for sharing their work. We all like folks to know we “did our homework.” We get our slides spiffed up and appropriately formatted for the webinar tool we are given. We time our remarks. We practice speaking clearly and at an appropriate pace.

The challenge this presents is that the end product puts the speaker and/or the organization at the center. We create an us/them dynamic before the event even starts. Think about set ups where the only ones who can use the voice tool to communicate are the organizers. Those who bear the presentation file are in control of the message. The tool administrator(s) control the process (i.e determining that they speak for 60 minutes, then there is Q&A.)

The use of a one way style of presentation reinforces the power dynamics of the speaker/expert/organization as central, and everyone else as “audience.” All too often, the audience is never heard. Is that a good use of precious synchronous time? Why not send out a video or narrated PowerPoint? An online gathering is time better spent as a multi-directional mode of “being together” — even online. This does NOT diminish the importance and value of content we “deliver” to others. Here are some options to consider.

Options:

- Move away from meetings that are primarily broadcast which holds control with the presenter. Sharing information is essential, but synchronous time should always have significant multi directional interaction. For my colleagues in international development, I think everyone has values of inclusiveness and shared participation. We have to “walk this talk” in webinars as well.

- Small things can create or break down us/them. For example don’t just show where you are on a map at the start of a webinar, add dots for all the participants and their locations. Better yet, use a tool that allows them to add their own dots. Help the group see not only you, but “we” – all the people working together about something we all care deeply about.

- Because we lack body language online, it is useful to really scrutinize our language.From the wording in the slides and by the speaker, consider changes in language so that it is more inclusive of the participants.

2. Strive for good practices for learning/engaging online. Webinars in general run the risk of being even less engaging than a dark room face to face with a long PowerPoint. There is a saying in the online facilitation world “A bad meeting F2F is a terrible meeting online.” So we need to be even more attentive to how we structure online engagements to reflect a) how adults learn b) the high risk of losing attention (especially due to multi tasking) and c) the cultural and power diversity inherent in your group. Quality content is important, but it alone is not a reason to use an interactive platform — you can deliver content in many ways. Choosing a synchronous mode, to me, implies interaction.

Options:

- Consider keeping online meetings to 60 minutes. If not, do a stretch break every at 30 and 60 minutes. Say “let’s take a 60 second break.” Stand up, stretch, look away from the screen and give your body a moment of respite. We’ll call you back in 60 (90-120) seconds (sometimes a bio break is useful!)

- A useful rule of thumb is to break up information presentation with some means of audience engagement/participation every 7-15 minutes. Use polls, chat, “red/green/yellow” feedback mechanisms, hand raising, checking for understanding, etc. This may mean you have someone facilitating these other channels if it is too distracting for the host and speakers. (Over time it does get easier, but practice is critical!)

- Take questions approximately every 15 minutes vs holding at end. People stop listening carefully and are thus less prepared to ask questions after longer periods of time. (They are also more prone to multitasking, etc.)

- Don’t just deliver information – use narrative. Stories hold our attention better than a series of bullet points. In fact, ditch those boring slides unless you are using the printed information to make it easier for people coming from a different first language.

- Deliver the useful content in a different manner and use the webmeeting entirely for questions and interactions. Send a recording introducing the team. Send a narrated PowerPoint about the topic. Keep these content packages smaller. For example, if you were trying to give an overview of a portfolio of projects, you could break it up into some sub packages. 1) about the team 2) strategy, 3) project descriptions, 4) monitoring and evaluation strategy, etc.

- Secondary tip: Do not think of these information products as polished products — don’t waste energy overproducing. That sucks the human element out of it. Imperfection is a door to engagement… seriously. Moments of uncertainty, tough questions — these engage the participants.

- Stay relaxed as a narrator and speak at useful pace for understanding, particularly for those who have English as a second (or third, fourth) language. Keep that human touch. Add little bits of personal information and affect. Be human.

- Let participants ask question verbally, not just in chat if possible. While there are many technical complications and sometimes the burden of accents on unclear audio channels, voice brings again brings in that human element. (Video does too, but there are bandwidth considerations. When you can, consider using it.)

- Encourage collective note taking in the chat room or with complementary tool. When people share this task, they listen more carefully and the begin to learn about each others strengths and insights as people add additional information or annotations.

- When someone asks a question, note who asked the question. This helps everyone see that people are heard, even if the audio option is not practical (for various reasons, no mic, etc. ) At the end of the call, specifically thank by name those who asked questions to encourage the behavior for future interactions.

- In Q&A sections, consider a visual to help people pay attention. Use the whiteboard for noting the questions, answers, links that refer to what has been spoken about, etc.

There are a few ideas. What are yours?

Also, here are some previous posts about similar issues:

- Quick Revisit of Web Meeting Tools – What is your favorite?

- What does it mean to facilitate an online meeting?

- Debrief: the role of visuals in online community management

- Synchronous Scheduling Trips in Larger Distributed Groups

- Telephone Conference Call Tips

- Designing and Facilitating Online Events (old, but still of some use…)

- What do we mean by engagement online?

- Raising the Bar on Online Event Practices

- Monday Video: Strange Meeting (and a few comments on teleconferencing)

- Why chat streams are critical to live events

Hi Nancy,

Great comments and insights. An area that strikes me about online communities versus face to face meetings is the power of questions, provocative statements or interesting artefacts. It’s interesting to see how a question can transform a group – a powerful question can take on a life of it’s own re-energizing a dormant group. I’ve watched this happen over the years with the online facilitators community. The more controversial, the better – conflict online which seems to be fast and furious provides incredible learning not too mention, engagement.

Awhile ago, I read about a posting on ebay about antique hair pins. Fascinating to see the number of hits this post received and each time someone added to the knowledge on antique hair pins – (an internal wiki for ebay, I suppose) Who woud have thought a posting on hair pins would have generated so much content and engaged a community of followers. I’m not certain how long the community stayed together but I’m also not certain this matters. Online communities was and wane, dropping in and out of conversations as they please – this peripatetic lifestyle drives dynamic dialogue and ensures engagement – (even if only, fleetingly

[…] White of Full Circle Associates has made a very useful blog post asking what we mean by engagement online. Nancy is the preeminent online facilitator, and her answers to her own question are a great outline […]

[…] in communities, vocational education and training at 4:51 am by ednavet Nancy White thinks that engagement in any community is on a spectrum from active participation in a group to […]

Nancy,

Your mention of tone is very important. In English classes we were hit with tone and many students did not get the message which is so important in this time of online and text communication. Since voice inflection is missing in online communication participants and facilitators must be very careful with their word choices. Since we are often in such a hurry to finish a task we often are careless with word choice. In face to face communication so many more cues are available.

Nancy,

In online learning, one of our hurdles is when we ask our participants to do group activities. Many balk and find reasons why they cannot get together with others for group activities online.

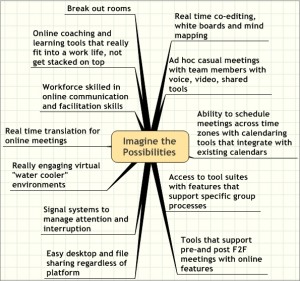

Seeing your concept of time online (thank you for the visual–it’s awesome), I wonder if you have some insight on quelling these “yeah, but” type responses to group activities in online learning. I think the problem is entangled in the time issue.

Cinde

Marcia, yes yes yes — I think in our hurry we cheat our own communications.

Cynthia, it is funny you mention this because this ended up be a topic of conversation in an online gathering this past week with a bunch of educators in Florida.

A couple of the things I do with “yea, but” are:

1. Start with small, well defined collaborative tasks that build up trust, reciprocity and visibility of the value and interdependence of group work. I find people will be less likely to “let down” someone they have gotten to know a bit. The socialization seems to matter (from my experience working with adults.)

2. Debrief the initial collaboration to identify what made it work/not work. Sometimes I ask tough questions like “what would happen if you did not participate in this activity?” or “what are the consequences of your non-participation.” (social pressure)

3. If the group is not being generative in the assignment, “flip it.” So ask for work that is counter productive to the desired outcome (which people often find amusing and think I’m joking). So if your goal was to design a lesson for 10th graders on Beethoven, ask them to design the perfect lesson where students would learn nothing. Absolutely nothing. What could faillsafe this goal? They generate the list. Then ask them how many things are in place for failure in the work they are doing now. Prioritise the top one or two things they can do something about and then they redesign their learning context to support, rather than defeat, participation (ask me questions if I did not explain that very well. ) I learned this from Keith McCandless – he calls it TRIZ.

[…] via Full Circle Associates » What do we mean by engagement online?. […]

[…] What do we mean by engagement online?- Full Circle, September 8, 2009 […]

[…] What do we mean by engagement online? | Full Circle Candace Whitehead, the Facilitator Support Specialist for the Florida Online Reading Professional Development project funded by the Florida DOE and housed at the University of Central Florida http://forpd.ucf.edu contacted me last month inviting me to participate in a web meeting with the cohort of online facilitators working in learning and particularly around literacy issues. The chance to have a conversation with practitioners is always an automatic YES for me. When we talked, Candace suggested the topic of “engagement.” This blog post is a little bit of “thinking out loud” prior to our conversation later this month. (tags: tm_picks IDEA engagement bestpractices online_learning online_facilitation) […]

[…] What do we mean by engagement online? | Full Circle […]

Nancy,

Enjoyed this post – and your experiences are quite helpful as this is the area that fascinates me most in virtual collaboration.

I have formed a collaborative learning group on Linked to explore this topic in a socially open forum. I hope you and your readers will consider joining and engaging with this group to share your experiences, knowledge and questions.

Here is a link to the group http://www.linkedin.com/groupInvitation?groupID=2350136&sharedKey=19C1004846E9

OR once signed into LI, search on groups for Radical Inclusion – Open Virtual Collaboration

All the best.

Nancy:

Wow, there’s some great stuff here. I’m a meeting and event professional that focuses on the education design of face-to-face and virtual experiences. I’ve been thinking for some time about how to make our face-to-face events more social, allowing more horizontal, peer-to-peer collaborative learning. So much of conference time is spent sitting passively in chairs listening to an expert “sage on the stage.” Participants want more dialogue and less monologue.

I’ve also been playing with hybrid meetings, integrating the virtual with the face-to-face to extend the learning experience and allow people to engage with each other and the content. So you’re post resonates with me a lot.

Dr. Davis Fougler calls “snowflake time” “supersynchrony.” He says supersynchronly allows online attendees to control the level of synchrony with parallel interactions, which magnifies learning opportunities and retention. No longer do learners need to use “turn-taking in discussions,” where words follow words, paragraphs follow paragraphs, people taking turns to speak. Instead of following a single one-way linear straight line fixed presentation, online learners have the ability to break and restore communication linearity. They can scroll back from the moment the statements was posted, while interacting presently in the here-and-now, resulting in several conversations happening all at the same time allowing for additional data flow and increased productivity. He and other researchers call this online productivity “bending time” or “hyper time through polylogues.”

Those of us that say that is information overload, too much information coming at us at once, have not yet mastered what many Gen X & Ys have: information synthesis. Information Synthesizers don’t feel overwhelmed by information – they either use it or they don’t, but they don’t whine that there’s too much. Oh, wait, that’s a different post than this one about engaging with content and people.

Thanks for being a springboard for more thinking and allowing me to run with some thoughts here.