My clients have been asking for more support in planning for the future. In almost every case there have been internal or external factors that suggest significant inflection or turning points. Policy changes due to political shifts. Growth in networks. Shifting priorities. Emerging possibilities. New combinations of partners.

My clients have been asking for more support in planning for the future. In almost every case there have been internal or external factors that suggest significant inflection or turning points. Policy changes due to political shifts. Growth in networks. Shifting priorities. Emerging possibilities. New combinations of partners.

They usually ask for traditional strategic planning. I have realized I don’t do this anymore. Won’t. Forget your SWOT analysis. I’m fully into the “liberating planning” space. A liberated facilitation space. This work has been deeply enhanced by my collaboration with folks like Keith McCandless and Fisher Qua, fellow “struturalistas!” Many of the words below came from or were inspired by them and others from the Liberating Structures community.

Context

Why do we need complexity informed planning? Three big reasons.

Why do we need complexity informed planning? Three big reasons.

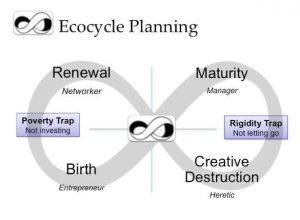

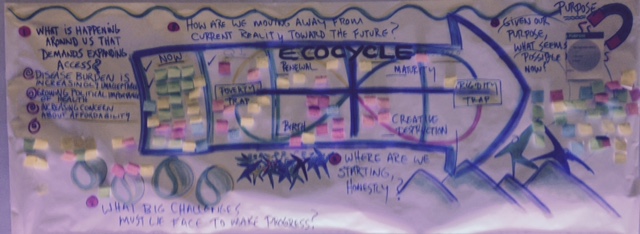

- Portfolios, not just projects: Very few organizations have just one element, yet planning is often linear and isolated at the project level. Strategically we need to take a portfolio perspective on planning which is quite different than “planning a project.” When you work at the portfolio level, you are looking not for a single success (or failure), but for signals that can show how to move the whole field forward. A portfolio approach can help buffer against the typical three-year grant funding cycles and keep focused on strategy. Tactics should include “safe fail” probes (http://cognitive-edge.com/methods/safe-to-fail-probes/) and experimentation in areas of uncertainty, and then, once some clarity has emerged, scale up or adapt to more mature results. Among many useful things, the Liberating Structure Ecocycle Planning (http://www.liberatingstructures.com/31-ecocycle-planning/ ) supports a complexity informed portfolio approach. Interestingly it also allows simultaneous work on strategy and tactics.

- Complexity requires complexity informed facilitation practices. A portfolio approach is complex, with many unknowns, variables and dependencies. Even within a project, the challenges people are facing are rarely simple cause/effect problems. They are complex. It does NOT mean that things are SO complex, we simply can’t address the complexity.The facilitation implication is that people need a handle on complexity, to recognize it, work with it, and not get overwhelmed by it. If we are to tackle system level problems, we need a repertoire suited for complex contexts. Look at the work of Cognitive Edge (http://cognitive-edge.com/ ) , Harold Jarche and many others. (http://jarche.com/2010/10/organizations-and-complexity/, https://jarche.com/2016/04/complexity-in-the-workplace/ , http://www.ontheagilepath.net/2015/10/complexity-and-methods-to-succeed-thanks-for-the-books-organize-for-complexity-and-komplexithoden.html and https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/resource-documents/10604.pdf )

Planning itself becomes an Ecocycle. My recent work with the Ecocycle Planning tool has opened a new repertoire of facilitating in complex contexts by helping us recognize that our work does, and should, span the four spaces of maturity, creative destruction,

Planning itself becomes an Ecocycle. My recent work with the Ecocycle Planning tool has opened a new repertoire of facilitating in complex contexts by helping us recognize that our work does, and should, span the four spaces of maturity, creative destruction,  networking and birth. The Ecocycle recognizes that we operate across a range of contexts and projects that are, from a Cynefin framework perspective, simple (rules based), complicated (expertise driven), complex (not predictable) and chaotic (we will never fully know!) A manager may feel most accountable for the maturity space, where tested approaches can be scaled up. But without an eye to the pipeline in, simply managing the mature space is self-delusion. It may require making space through creative destruction. Opening up to wider networks to identify new possibilities and steward them through the innovation process. Yet maturity is the manager’s area of comfort. To embrace the other areas, they must see the action of the continuum of the Ecocycle. (EDIT: For some great background on Ecocycle see https://www.taesch.com/references-cards/ecocycle by Luc Taesch!)

networking and birth. The Ecocycle recognizes that we operate across a range of contexts and projects that are, from a Cynefin framework perspective, simple (rules based), complicated (expertise driven), complex (not predictable) and chaotic (we will never fully know!) A manager may feel most accountable for the maturity space, where tested approaches can be scaled up. But without an eye to the pipeline in, simply managing the mature space is self-delusion. It may require making space through creative destruction. Opening up to wider networks to identify new possibilities and steward them through the innovation process. Yet maturity is the manager’s area of comfort. To embrace the other areas, they must see the action of the continuum of the Ecocycle. (EDIT: For some great background on Ecocycle see https://www.taesch.com/references-cards/ecocycle by Luc Taesch!)

The patterns I notice across the Ecocycle and other useful facilitation processes for working in a complex context are that:

- they ask us to shift our perspective about how past experiences inform our present analysis,

- they support the emergent (often unpredictable), and,

- they are iterative.

Another thing I notice is that this practice embraces a different mindset for planning which also attracts REALLY INTERESTING people. That, of course, attracts me.

The Adaptive Strategy Landscape for Project Design & Development

We have been struggling about what to call this and how to describe it. My newest experiment is “Adaptive Strategy Landscape.” I’m currently designing a workshop for practitioners in international development to use Liberating Structures in project design – thus my need to blog about this and think out loud with you. I am drawn to the term “landscape” because it is visually strong, and implies an ecosystem of inter-relating elements. I am very open to other name suggestions. 😉

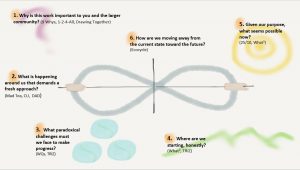

So what does this Landscape, this “emergent, complexity-friendly strategic planning” actually look like? Right now we are framing it around six questions I learned from Keith. Typically I tinker and modify them to the domain in question. This is their generic form.

- PURPOSE: Why is this work important to us and the wider community? How do we justify our work to others? What makes this important?

- CONTEXT: What is happening around us that demands change? This question is particularly energizing to help identify and sharpen purpose. It shocks me how often this is ignored or left muddy and far from strategic. A good idea out of context is often a blind alley.

- BASELINE: Where are we starting, honestly? This question has many layers and process options, from identification of strengths (things in our “Maturity area” of the ecocycle), positive deviance (http://www.liberatingstructures.com/10-discovery-action-dialogue/ ) , identification of challenges, or the things we have resisted or feared discussing, the light and the dark. It surfaces the things we must work with. AND the things we need to creatively destroy to make space for innovation. The creative destruction is ESSENTIAL to this process!

- CHALLENGE: What paradoxical challenges must we face to make progress? This invites the ground shifting conversation to enable working in a complex environment. It is not “if we do X, Y will happen.” It is not X or Y. It examines competing priorities, uncertain futures, and antagonizing circumstances. It explores multiple perspectives and truths. Paradoxes are not things to defeat us, but tools to change how we view a problem. To shift our mindsets. A useful sub-question if things get stuck is What happens if we don’t change? How do we keep moving forward in this land of “wicked questions?” ( http://www.liberatingstructures.com/4-wicked-questions/ )

- AMBITION: Given our purpose, what big ideas seem possible now for our purpose? What big opportunities do we see? What is ready to be imagined and then stewarded into birth? This frames our shared impetus forward. It is the genesis of our monitoring and evaluation framework as well, informed by the other five questions. This is super-important and includes a developmental evaluation perspective right from the start. This is useful to engage project funders in dialog, both in the proposal, planning and discussion of outputs and outcomes from a complexity perspective.

- ACTION: How are we moving away from the current state to our desired future state? This is the practical piece. What are the next steps? Things we can decide and do. Start now, no matter how small the step. Do something. Don’t wait to plan for perfection. ACT! Build iterative learning into the design. Monitor and evaluate as a way of working, not an afterthought or a tick on the checklist.

While these each have a number attached to them that informs sequence, this is not by any means always a linear process. A discovery around “where are we starting, honestly,” may lead us to rethink our purpose. Learning loops abound.

Process

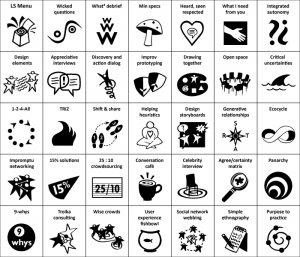

A portfolio approach, complexity and the Ecocycle, informed by the six questions, has lead to the construction of a set or “string” of processes (many from Liberating Structures) that inform design of the process.Here are some example structures for each question.

- PURPOSE: Why, why, why is this work important to us and the wider community?

- CONTEXT: What is happening around us that demands a fresh/new/novel approach ?

- BASELINE: Where are we starting, really?

- CHALLENGE: What paradoxical challenges must we face to make progress?

- AMBITION: Given our purpose, what seems possible now?

- ACTION: How are we breaking away from the present and moving toward the future?

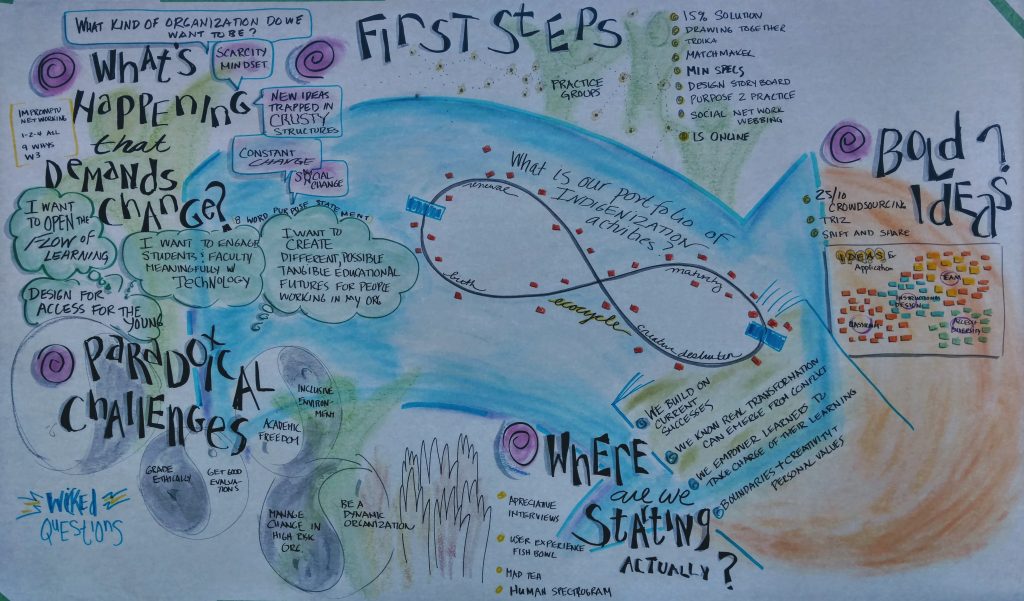

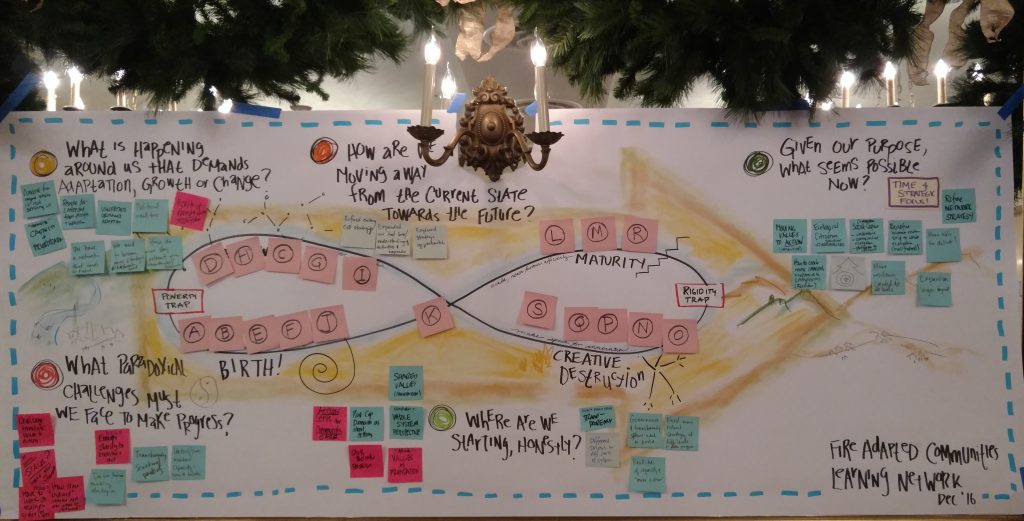

I pay close attention to turning points, where something shifts in the group, and adjust my string to respond to these emergent factors. I use large visuals to anchor and capture salient information, ideally identified by the participants and NOT me. (This helps avoid one of my pitfalls, over-harvesting!) Post its, paper, pens are all in everyone’s hands. Fisher has started adding a timeline to the bottom to build off of question 3 with more detail.

We iteratively stop and take turns telling the story of the emerging visual to get clear on what we understand and what we need to process further. Often, this is the moment when we go back and sharpen the purpose, and find the right level of granularity around each question. Sometimes we capture these on videos. There are moments when you see new clarity emerge right on the spot.

From this a smaller team usually transforms this into a written plan, conforming (ahem!) to the needs of the organization and or funders. There is still a gap between the very learning intensive process of complexity-based planning and the formats we use to write, manage and evaluate projects. More work to do!

Here are a few examples of the visual after a planning session.

So what do you think?

Please add, comment, critique, rename in the comments! Thank you in advance for thinking WITH me!

Resources/Inspirations:

- Plan in Uncertainty: A Case for Strategic Adaptive Action

http://www.hsdinstitute.org/resources/plan-in-uncertainty-strategic-adaptive-action.html - Swat your SWOT Forever http://matthewemay.com/swat-your-swot-forever/

Innovation Barrier #2: Your Network Is Embedded In An Older Model

At this point, most people are aware of the power of network effects. Everybody uses Microsoft Office because everyone else uses it. If you want to sell something, you put it on eBay because that’s where the buyers are (and they’re there because that’s where the sellers are). Apple’s iOS is popular, in part, because everyone wants to develop for it.

via 3 Things That Can Stall Innovation (And How To Overcome Them) | The Creativity Post.