My week facilitating #change11, a very massive MOOC, flew by too fast for me to blink. (See these previous posts for more background.) Between being on the road so much and the distributed nature of the conversations, my head was spinning by Friday and it has taken until today to slow down, reflect and write. I’d like to reflect on both the content and process of “week 8” where we focused mostly on the idea of “social artists” in learning and technology. Well, honestly, mostly just on the social artist bit. As always, I was too ambitious in my planned scope. I am happy it narrowed down to social artists. That was enough!

My week facilitating #change11, a very massive MOOC, flew by too fast for me to blink. (See these previous posts for more background.) Between being on the road so much and the distributed nature of the conversations, my head was spinning by Friday and it has taken until today to slow down, reflect and write. I’d like to reflect on both the content and process of “week 8” where we focused mostly on the idea of “social artists” in learning and technology. Well, honestly, mostly just on the social artist bit. As always, I was too ambitious in my planned scope. I am happy it narrowed down to social artists. That was enough!

First, the process. #Change11 is structured around whatever theme or idea the facilitator of the week offers. Up until now that has been kicked off by a piece of writing, a recording or some structured artifact where the facilitator shares his or her big ideas around change, technology and learning. There is at least one synchronous event per week (more often two) hosted on the platform formerly known as Elluminate (now BB Collaborate, and I think worse for the transition). There is the #Change11 daily which aggregates posts from the lead facilitators (George Siemens, Stephen Downes and Dave Cormier), posts and tweets tagged with #Change11. There are some quasi-centralized discussion outposts on Facebook, Google+ (see this tool to find Change11 circles on G+) and Moodle, but most of the action seems to be on blog posts/comments and Twitter. In other words, the landscape one might traverse for learning and sensemaking is broad and diverse. I’m not the only one trying to make sense of this. See “We are always catching up” http://squiremorley.wordpress.com/2011/11/04/change11-playing-catchup-part-3/#comment-190 and https://jennymackness.wordpress.com/2011/10/26/the-selfish-blogger-syndrome/#comment-1666

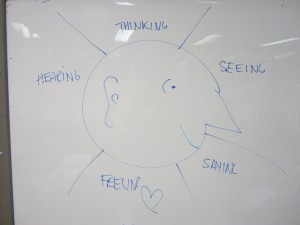

Of course, I didn’t structure my week around a piece of writing. I was interested in explore the experience of change and how the social artist plays a role in that experience. Instead of content slides, I ginned up a deck full of questions and whiteboard templates inviting people to express themselves together visually, textually and if so moved, to grab the mic. (The before and after slides are here, but don’t expect them to make much sense as a stand alone presentation, and more like digital traces of what we did together. ) I ended with a challenge to find stories of social artists in their learning lives and to blog and or tag them #socialartist. And of course I scheduled both session late in the game, giving few time to get it on their calendar. Did I mention I have been busy? Can you read my sense of guilt between the lines? Yup. Giulia Forsythe then invited me to a follow up session later on Monday, and we had a final hour on Friday where George and Stephen interviewed me which was both interesting and weird. I think I got a little verclempt. Ahem! Judge for yourselves!

I then tracked tags to try and read and comment on most of the blogs that either blogged in general on the #socialartist idea or took up my challenge. Here are a few of the links (and yes, I’m still catching up commenting on some of them! DO look at the comments in these posts! Lots to think about)

Here are some of the tweets archived into a Tweetdoc.

So now the content. The alleged synthesis and sense making. NOT! I don’t think I can do it, but here are the things that have been emerging for me through all these distributed conversations.

What IS a social artist?

So, what is a social artist and why did I think it might be relevant to #Change11? I’m not sure we landed on a clear definition. I started with the concept I borrowed from Etienne Wenger-Trayner, who has talked about the social artist as a person who makes the space for the social aspect of learning. Here is a quote from him from 2008 on David Wilcox’s blog which really resonates for me:

So, what is a social artist and why did I think it might be relevant to #Change11? I’m not sure we landed on a clear definition. I started with the concept I borrowed from Etienne Wenger-Trayner, who has talked about the social artist as a person who makes the space for the social aspect of learning. Here is a quote from him from 2008 on David Wilcox’s blog which really resonates for me:

“The key success factor we’ve found is learning citizenship where learning citizenship is a personal commitment to seeing how we are as citizens in this world. Let me give you an example: I know an oncological surgeon in Ontario, Canada who asks himself how to provide the social infrastructure for patients to learn about cancer. An act of learning citizenship is to be able to use who you are to open this space for learning. I’ve come to call these people social artists, people who can create a space where people can find their own sense of learning citizenship.

“I love social artists. In fact I worship them. First because social artists know how to do what I only know how to talk about; and second because I care about the learning of this planet. I think we are in a race between learning and survival. We live in a knowledge economy where any expertise is too complex for any one person. One person can’t be an expert so anyone who can give voice to that need to work together is a social artist.

“I do a lot of consultancy work for training community leaders, but in my heart of hearts I know the real secret of those social artists is not something I can teach. The real secret of those people is knowing how to use who you are as a vehicle for opening spaces for learning. I don’t really have the words – but I just know when I see it. It is a way of tapping into who you are and of making that a gift to the world … it’s about being able to use who I am to take my community to a new level of learning and performance.

“I want to leave you with three questions…

- How can you act as a learning citizen in this world?

- How can we as a group help , sustain, celebrate that capability among ourselves? If EQUAL has done a bit of that – how do we capture it, nurture it cherish it?

- For those of you who are movers and shakers – how can you build an institutional structure that enables people to find their voice in the interests of the people they want to serve? Social artists need to fight … How can we enable a structure that enables those people to do the work that they do?

“These are urgent questions. Social innovation is a matter of the heart, not just projects. We need you to do that for the world, not just Europe”.

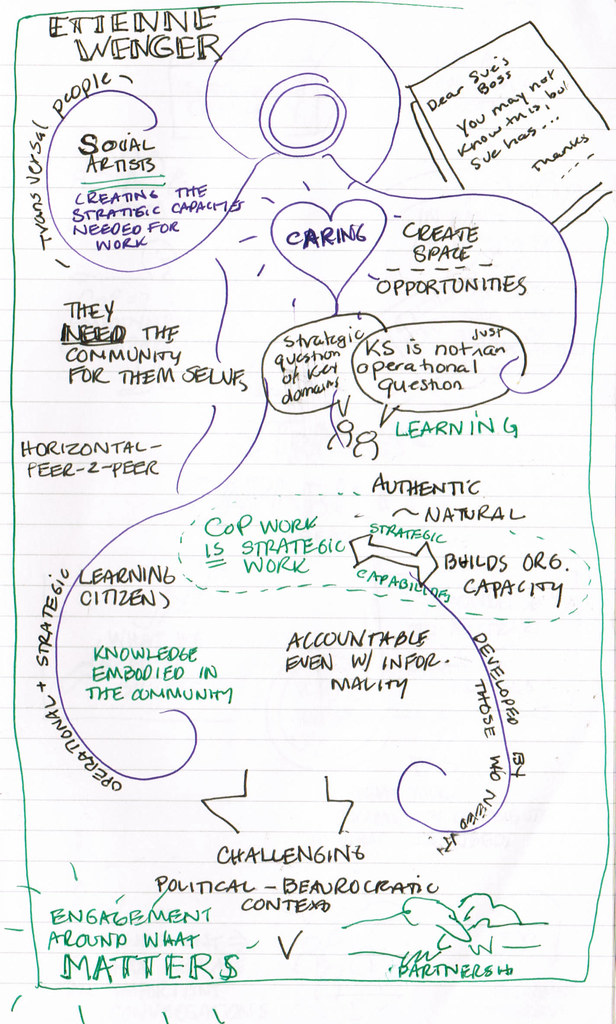

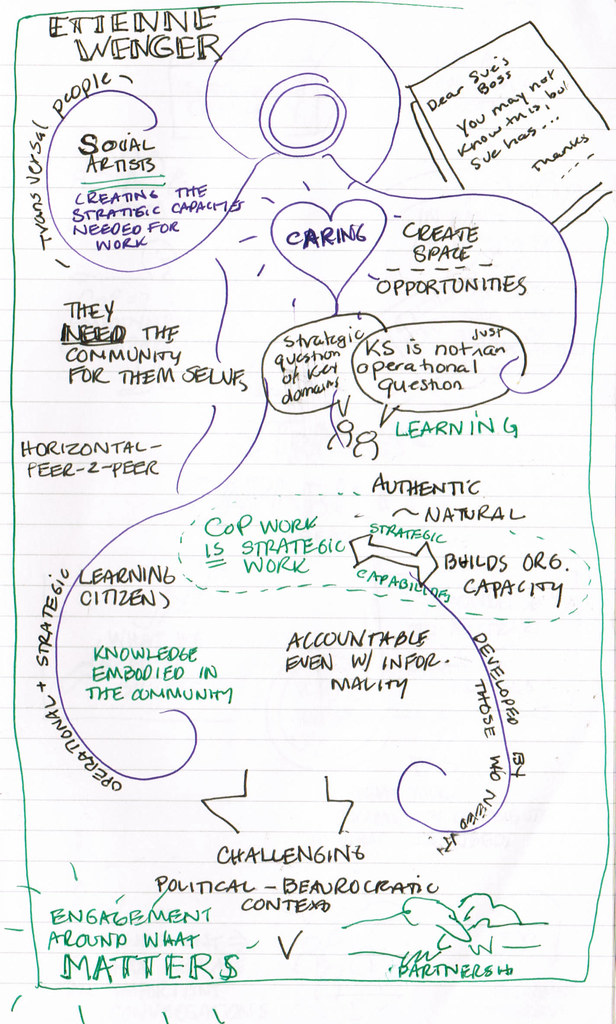

You can also hear Etienne talk about social artists (as well as other community issues) in this keynote from September’s ShareFair in Rome. The sketchnote above is from that session.

Jean Houston defines social artistry as:

Social Artistry is the art of enhancing human capacities in the light of social complexity. It seeks to bring new ways of thinking, being and doing to social challenges in the world.

…Social Artists are leaders in many fields who bring the same order of passion and skill that an artist brings to his or her art form, to the canvas of our social reality. (See also the Jean Houston Foundation page)

As I juxtapose Etienne and Jean’s meanings of the concept, I am finding out how to link the roles to learning. From Etienne’s questions “How can you act as a learning citizen in this world? How can we as a group help , sustain, celebrate that capability among ourselves?” I hear the call to recognize the social acts of learning more explicitly and to attend to the people with social artistry skills. Nurture and recognize them. At the least, remove barriers to their participation. From Jean, I glean the parallels of passion and skill from art forms, to the social canvas.

The other thread was the juxtaposition of “social” and “artist” — where some had the concept of the solo artist, working alone to create a product of their work, while here the canvas is not only ephemeral through the interaction of people, but the role is inherently WITH people and social, not solitary. One person also noted the tension between the idea of a scientist and an artist which is to me one of the artificial constructs we create by dividing art and science. They have roots which intermingle.

Here are some links where people really picked up on the art part, which thrilled me.

In case you want more on visual practices, check out https://onlinefacilitation.wikispaces.com/Visual+Work+and+Thinking

Why is social artistry useful?

As the week went on and we sought out examples of social artists, and as we did this, I also realized it was useful to tease apart the social artist as a person (their role, skills, talents, way of being in the world) and the practices of social artistry which are often named as process arts, facilitation, network weaving, etc. People pointed a lot to specific practices, like the power of engaging people in using the white board in the online webinar space, how to use both silence and music instead of talking all the time, commenting on others’ blogs, helping them feel heard, designing connecting out into the world into her classroom, asking great questions, and such. I think people really resonated with these familiar practices, but we struggled with the less tangible ones. Like the kinds of people who just open up and hold space for people to be together and learn. The people who do that lightly and without manipulation. The people with big ears, big hearts and generosity of spirit. How do you tie that tangibly to education when we haven’t a clue how to measure it and I think many of us wonder if it can be learned, or it is something some of us just carry with us. The “fluffy bunny” stuff which I know, in my heart, is not fluffy at all, but very profound. I have seen the difference “being seen, heard and loved” means to people. But I can’t call it out in clear, intellectual terms that some people sought. I could not answer them. At the same time, I felt a quick kinship to those who recognized it. Are we finding our tribe? I don’t know.

Finally, it was very interesting to note that both the experiences of the synchronous gatherings (particularly the first one) and the concept of social artistry really seemed to resonate with some people, baffle some people and find no relevance for others. This was VERY interesting to me. In The Queen Has No Clothes, George wrote about feel-good commentating:

This week’s MOOC #change11 has not held my interest. Without doubt, Nancy White is a charismatic facilitator, using graphical tools to have participants express themselves and develop a particular view. I think this approach (using such graphical tools) is excellent for the participants.

I learned long ago that my wonderfully produced mathematical notes were excellent – for me. The iterrative process of producing these and improving them was valuable to me, the writer. My students needed to produce their own versions (yes, to construct their own knowledge), for this to be valuable for them. So the outcome of the process did not mean much without being a participant.

Also, there seemed to be an inordinate amount of “feel-good” commentating. Why? Could there be a cultural difference?

Hence my Tweet: the Queen has got no clothes on. There, I said it.

Tonight I responded:

I’m still chewing on what I understand to be underneath – the lack of resonance for you (and others!) about social artistry in the context of change, learning and technology.

When we moved into “interview Nancy” mode during the Friday session and George started asking me questions which felt more academic to me, I started to get some insight into the fact that while I know “inside” what social artistry is because I believe I practice it, I still can’t clearly articulate it in a way that fits in with learning theories and the deeper, intellectual grounding that many of you have. I’m a simple practitioner. So making that leap is .. well, hard.

As I listened to today’s session w/ Dave and rhizomatic learning, I kept being troubled by his reference of the rhizomatic learner as a nomad. The metaphor of the nomad — at least the romanticized notion of a nomad is a solitary being, forging off on her or his own.

This has a disconnect for the social aspect of learning for me. I’m not saying all learning must be in a social context, but a heck of a lot of it is. Those who pay attention to making that space where this learning happens play and important role. Thus the social artist.

We ran out of time and never got to the transversalist. That’s another interesting kettle of fish!

I need to go back and dig into what George meant about “feel good comments” — what makes a comment feel-good? What other qualities of comments might we use or name? A whole ‘nuther interesting thread.

The loose ends…Onward

You know what they say. Once you start looking for something you had not noticed before, you start to see it everywhere. Like when I became pregnant with my first child, I saw pregnant women everywhere where before they didn’t even show as a blip on my radar screen. So as the week went by, I kept Tweeting related #socialartist links. For example, not change11 directly, but related social artist practices from Barbara Ganley http://community-expressions.com/2011/11/04/lessons-learned-part-one-listening/ and from the Facebook Convo, an link to http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Habitus_(sociology) from Vanessa Vaile who wrote “PS I see strong traces of habitus in Digital Habitats” which of course tickled me! I can even see glimpses of social artistry in this more general reflection on Change11 https://bigreturns.posterous.com/change11-looking-forward-and-looking-back

Habitus is the set of socially learnt dispositions, skills and ways of acting, that are often taken for granted, and which are acquired through the activities and experiences of everyday life. Habitus is a complex concept, but in its simplest usage could be understood as a structure of the mind characterized by a set of acquired schemata, sensibilities, dispositions and taste.[1] The particular contents of the habitus are the result of the objectification of social structure at the level of individual subjectivity. Hence, the habitus is, by definition, isomorphic with the structural conditions in which it emerged.

The concept of habitus has been used as early as Aristotle but in contemporary usage was introduced by Marcel Mauss and later re-elaborated by Pierre Bourdieu. Bourdieu elaborates on the notion of Habitus by explaining its dependency on history and human memory. For instance, a certain behaviour or belief becomes part of a society’s structure when the original purpose of that behaviour or belief can no longer be recalled and becomes socialized into individuals of that culture.

Habitus is the set of socially learnt dispositions, skills and ways of acting, that are often taken for granted, and which are acquired through the activities and experiences of everyday life.Habitus is a complex concept, but in its simplest usage could be understood as a structure of the mind characterized by a set of acquired schemata, sensibilities, dispositions and taste.[1] The particular contents of the habitus are the result of the objectification of social structure at the level of individual subjectivity. Hence, the habitus is, by definition, isomorphic with the structural conditions in which it emerged.The concept of habitus has been used as early as Aristotle but in contemporary usage was introduced by Marcel Mauss and later re-elaborated by Pierre Bourdieu. Bourdieu elaborates on the notion of Habitus by explaining its dependency on history and human memory. For instance, a certain behaviour or belief becomes part of a society’s structure when the original purpose of that behaviour or belief can no longer be recalled and becomes socialized into individuals of that culture.

Here are some other places where Social artistry appeared in front of me this week

Want more #Change11? The schedule is here.

The beauty of a MOOC is the way you can sail into ideas, people, memes, and streams. Here are some people and their streams I want to read more of:

Alan Levine has a great new video shared via the Flat Classroom Project that took me back to some thinking I did with some pals at the University of Reading’s OdinLab (UK) in 2010. We were pondering how to talk about identity, particularly in the internet era. The OdinLab folks had a project for university students called “This is Me” and I did a remix for Librarians as part of some work I was doing in the US.

Alan Levine has a great new video shared via the Flat Classroom Project that took me back to some thinking I did with some pals at the University of Reading’s OdinLab (UK) in 2010. We were pondering how to talk about identity, particularly in the internet era. The OdinLab folks had a project for university students called “This is Me” and I did a remix for Librarians as part of some work I was doing in the US.

So, what is a social artist and why did I think it might be relevant to #Change11? I’m not sure we landed on a clear definition. I started with the concept I borrowed from Etienne Wenger-Trayner, who has talked about the social artist as a person who makes the space for the social aspect of learning. Here is a quote from him from 2008 on

So, what is a social artist and why did I think it might be relevant to #Change11? I’m not sure we landed on a clear definition. I started with the concept I borrowed from Etienne Wenger-Trayner, who has talked about the social artist as a person who makes the space for the social aspect of learning. Here is a quote from him from 2008 on